Lymph Node Metastases of Prostatic Adenocarcinoma in the Mesorectum in Patients with Rectal Cancer

Article information

Abstract

Lymph node involvement is the most important prognostic factor of rectal cancer. Cancer originating from sites other than the rectum rarely metastasizes to the mesorectal lymph node. We report a rectal cancer patient with a synchronous metastatic prostatic carcinoma to the mesorectal lymph node.

INTRODUCTION

Lymph node metastases are an important prognostic factor following surgery for rectal cancer. Therefore, meticulous examination of the mesorectal lymph node is essential. Metastasis to the mesorectal lymph node from other sites, with the exception of the anus and rectum, is very rare. Prostatic cancer is the second most common cancer in males in Western countries. Despite the incidence of prostatic adenocarcinomas, the propensity for metastatic spread and reports on the unusual locations of lymph node metastases are very rare (1). In addition, mesorectal lymph node metastasis from sites other than the rectum has rarely been reported (2). We report a case of rectal cancer in a patient with synchronous metastatic prostatic cancer in the mesorectal lymph node. This case report appears to be the second report of lymph node metastasis to the mesorectum from a prostatic adenocarcinoma documented in the English literature.

CASE REPORT

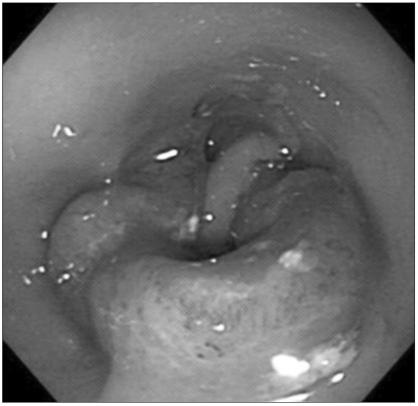

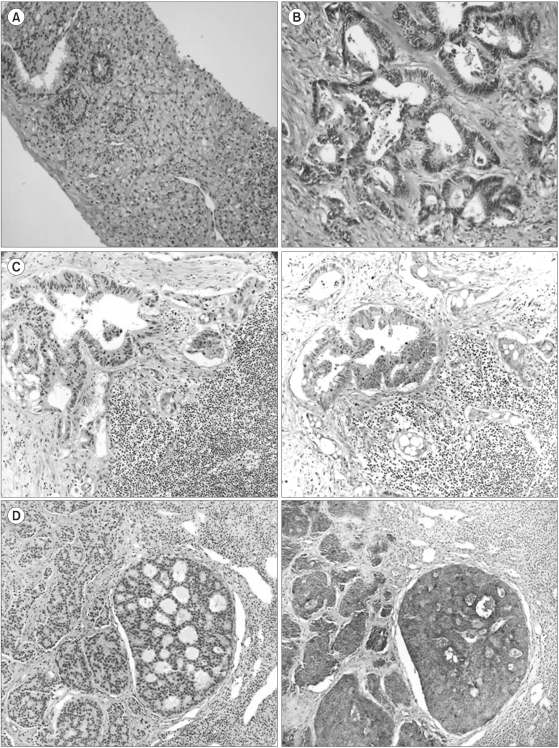

A 76-year-old man presented with a 2-month history of constipation and defecation difficulty. He also complained of voiding difficulty. He had no family history of colon or related cancer. On manual rectal examination, a hard mass, without a mucosal lesion, was palpated on the ventral side. CT scans showed an encircling mass, with perirectal infiltration at the rectosigmoid junction and a mass at the prostate (Fig. 1). The patient subsequently underwent a colonoscopy, which revealed an obstructing mass in the rectosigmoid area (Fig. 2). The biopsy performed on the rectal mass showed an adenocarcinoma, with moderate differentiation. Because of the mass lesion at the prostate on CT scan, a needle biopsy was performed for this lesion. The needle biopsy revealed a prostatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3A). The patient underwent a low anterior resection for rectal cancer, and was consulted to a urologic surgeon for the prostatic lesion, who decided to perform postoperative radiotherapy and hormonal therapy.

CT scan shows the encircling mass at the rectosigmoid junction. (A, B, C) An obstructing mass in the distal sigmoid colon. (D) Mass lesion in the prostate.

(A) The adenocarcinoma in the prostate, composed of cuboidal or columnar clear cells with a cribriform pattern. (B) The adenocarcinoma in the colon, with a complex glandular structures and pleomorphic columnar cells. (C) Right; The colonic adenocarcinoma metastasing to a lymph node. Left; The colonic adenocarcinoma is negative for PAP on immunostaining. (D) Right; The prostatic adenocarcinoma metastasizing to a lymph node. Left; The prostatic adenocarcinoma is positive for PAP on immunostaining.

A 5.3 cm sized encircling ulcerofungating mass was present in the low anterior resection specimen. This was a typical colonic adenocarcinoma, moderately differentiated, invading the entire rectal wall, with accompanying metastasis to the lymph nodes. The lymph nodes showed metastasis of another adenocarcinoma, with a different microscopic pattern. The tumor was composed of cuboidal or columnar cells, with clear pale cytoplasm and round nuclei in a small glandular, cribriform or diffuse infiltrative pattern (Gleason grade 9). From immunostaining, they were positive for PSA and PAP, prostatic markers, while the colonic adenocarcinoma cells were negative for these markers (Fig. 3).

He recovered uneventfully. After recovery, he underwent radiotherapy and hormonal therapy for prostatic cancer, and has been followed up without evidence of recurrence for 15 months.

DISCUSSION

The prostate is richly supplied with lymphatics, which drain into the obturator-hypogastric and presacral nodes (3). Micrometastasis to these lymph nodes is known as a probably early and frequent event, with a clinically localized carcinoma of the prostate detected with high incidence involving a node in these two groups (4). In contrast, as far as we could determine in a search of the literature, lymph node metastasis of a prostatic carcinoma to the mesorectum has been reported only once before (2).

In our case, PSA and PSAP were both strongly positive in the tumor cells of the lymph node. Staining of nonprostatic epithelial cells for PSA has been reported (5,6); however, it was found that these false staining were caused by a batch of faulty antiserum (7).

These observations of lymph node metastasis of a prostatic adenocarcinoma in the mesorectum show that a lymphatic connection could exist between hypogastric lymphatic drainage and mesorectal drainage. Actually, an extension of a rectal adenocarcinoma to extra-mesenteric lymph nodes was documented many years previously (8). Therefore, lateral node dissection has been advocated, even for advanced rectal carcinoma, at or below the peritoneal reflection (9). Moreover, there is no reason to believe that such drainage would be preferentially from the prostate to the mesorectum, rather than from the rectum to extramesenteric lymph nodes. Such a hypothesis would partially explain the high numbers of local recurrence found in cases of low rectal cancer (10).