Prognostic Significance of Serum Carcinoembryonic Antigen Normalization on Survival in Rectal Cancer Treated with Preoperative Chemoradiation

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this retrospective study was to identify factors predictive of survival in rectal cancer patients who received surgery with curative intent after preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT).

Materials and Methods

Between July 1996 and June 2010, 104 patients underwent surgery for rectal cancer after preoperative CRT. The median dose of radiotherapy was 50.4 Gy (range, 43.2 to 54.4 Gy) for 6 weeks. Chemotherapy was a bolus injection of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin for the first and last week of radiotherapy (n=84, 77.1%) or capecitabine administered daily during radiotherapy (n=17, 16.3%). Low anterior resection (n=86, 82.7%) or abdominoperineal resection (n=18, 17.3%) was performed at a median 47 days from the end of radiotherapy, and four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy was administered. The serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was checked at initial diagnosis and just before surgery.

Results

After a median follow-up of 48 months (range, 9 to 174 months), 5-year disease free survival (DFS) was 74.5% and 5-year overall survival (OS) was 86.4%. Down staging of T diagnoses occurred in 32 patients (30.8%) and of N diagnoses in 40 patients (38.5%). The CEA change from initial diagnosis to pre-surgery (high-high vs. high-normal vs. normal-normal) was a statistically significant prognostic factor for DFS (p=0.012), OS (p=0.002), and distant metastasis free survival (p=0.018) in a multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Patients who achieve normal CEA level by the time of surgery have a more favorable outcome than those who retain a high CEA level after preoperative CRT. The normalization of CEA levels can provide important information about the prognosis in rectal cancer treatment.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer patient number has been going up continuously since 1975 (above 500,000). Factors that are known in particular to increase a person's risk to develop this cancer are as follows: an individual's age, dietary habits, any complaint of obesity, diabetes, previous history of cancer or intestinal polyps, personal habit of alcohol consumption and smoking, family history of colon cancer, race, sex, and ethnicity. In recent years, the mortality rate from colorectal cancer has become higher in Korea and it is now the third leading cause of death from cancer [1].

Among colorectal cancer, rectal cancer is a candidate for chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in many cases. Recent advances in surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy have contributed to the improvement in the management of rectal cancer. These advances have translated into improved rates of local control, survival, and quality of life. Preoperative CRT has been increasingly used in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer and has now become a standard component of multimodal treatment [2-6]. A prospective randomized trial confirmed that preoperative CRT, compared with postoperative radiotherapy, improved local control and was associated with reduced toxicity [2,7]. Despite these advances, approximately 40% of patients who undergo resection with curative intent will still die from either local recurrence and/or distant metastasis [8]. Therefore we should identify factors that can anticipate poor outcomes and those patients that will need intense adjuvant therapy.

Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is the tumor marker used most widely as an indicator of disease progression or recurrence after resection of a primary tumor. Preoperative CEA concentration is currently regarded to be important in assessing the prognosis for patients with rectal cancer [9-12]. It is a standard measure that is easily accessible and inexpensive. There have been some reports investigating whether the serum CEA level can predict the response to preoperative CRT in rectal cancer [13-16], but it has not been proven that normalization of the CEA level after preoperative CRT predicts survival. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of changes in CEA on recurrence and survival as well as on other prognostic factors through checking the CEA level both before and after CRT.

Materials and Methods

1. Patient population

From July 1996 to June 2010, 132 patients with histologically confirmed, locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma underwent preoperative CRT followed by surgery. The exclusions included eight patients with distant metastasis at the time of the pretreatment workup, five patients who underwent transanal local excision, ten patients who were lost in follow-up, and five patients who had missing data of CEA. Remaining were 104 patients with stage II and III rectal cancer who were included in our study and treated with preoperative CRT followed by surgery.

All patients underwent staging workups including digital rectal examination, flexible endoscopy, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scans, bone scans, a complete blood count, liver enzymes, and serum CEA. Clinical staging was based on CT images and regional lymph nodes were classified as N1 (1-3 positive) or N2 (≥4 positive) according to the criteria of size (5 mm) and morphology (irregular margin). If further workup was needed, magnetic resonance scanning of the pelvis, liver, or positron emission tomography was used.

2. Treatment

All patients received preoperative CRT. The radiotherapy consisted of a whole pelvic dose of 45 Gy and a booster dose for the primary tumor up to 50.4 Gy (range, 43.2 to 54.4 Gy). The radiation was delivered with the patients in a prone position, five days per week for six weeks with a daily fraction of 1.8 Gy. Three individually shaped fields (posterior and bilateral fields) or a four-box technique (anterior-posterior and bilateral fields) with beam energies of 6 MV or 10 MV were used. Chemotherapy was a bolus injection of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin (LF) (n=81, 77.9%) or LF plus oxaliplatin (n=6, 5.8%) for the first and last week of radiotherapy, or capecitabine administered daily during radiotherapy (n=17, 16.3%). Chemotherapy was withheld if grade 3 or greater neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or liver toxicity developed. All patients underwent surgery at a median of 57 days (range, 17 to 99 days) after the end of preoperative CRT. Low anterior resection (LAR) (n=86, 82.7%) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) (n=18, 17.3%) was performed by four colorectal surgeons. After surgery, four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy was done. There were 79 cases (76%) of LF and 11 cases (10.6%) of capecitabine for adjuvant chemotherapy. Fourteen patients did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy due to old age, renal failure, stroke, or poor performance. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before treatment. Our Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this retrospective study.

3. Follow-up and response evaluation

Clinicians evaluated the patients weekly during treatment by physical examination and the appropriate blood tests. The patients were examined at 2 weeks and then at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months for the first year, then every 6 months for the next 2 years. After 2 years, patients were checked annually until 5-year post-surgery.

Treatment outcomes were evaluated as follows: Downstaging was defined as the lowering of the T and N stages between the pretreatment CT and the pathology report stage. The serum CEA level was checked by immunoradiometric assay (Immunotech IMA, Prague, Czech Republic) at initial diagnosis and just before surgery. CEA level of 4 ng/mL was adopted as the cut off level. Local failure was defined as any recurrence in the pelvic radiation field, and distant metastasis as outside the radiation field. Disease free survival (DFS) was calculated from the end of treatment to the time of local or distant failure. Overall survival (OS) was censored at the time of death of a patient or at the end of follow-up.

4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used SPSS ver. 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All prognostic factors were examined by univariate analysis. Null hypotheses of no difference were rejected if p-values were less than 0.05, or, equivalently, if the 95% confidence intervals of risk point estimates excluded 1. Distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) and OS rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared with the log-rank test. In a multivariate analysis, factors with a p-value less than 0.25 in a univariate analysis were included for analysis. The Cox proportional hazards model was used in the multivariate analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. The study cohort consisted of 71 males and 33 females. The median age was 55 years (range, 28 to 85 years). The median longitudinal distance between the tumor margin and the anal verge was 5 cm; 45 patients (43.3%) had more than 5 cm between the tumor margin and the anal verge. The status of margin included proximal, distal, and circumferential margin. LAR was performed in 86 patients (82.7%). Eighteen patients (17.3%) underwent APR. Sixty-three patients (60.6%) had pathologic T3. The median tumor size was 4.75 cm (range, 0.5 to 6.7 cm). Sixty patients (57.7%) had N0 pathology. Eighty-five patients (81.7%) underwent lymph node dissection less than 12.

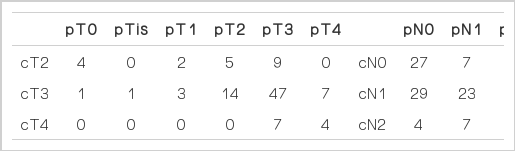

A comparison between the clinical stage before preoperative CRT and the pathologic stage after surgery are described in Table 2. The pathologic T stage after surgery was T0 in five patients and Tis in one patient. Tumor down staging occurred in 32 cases (30.8%). A decrease in the nodal stage was observed in 40 patients (38.5%). Sixty patients (57.7% of the cases in the study) were staged as pN0. Among 32 patients who had elevated CEA levels at initial diagnosis, CEA normalization occurred in 27 and elevated CEA levels were persistently observed after surgery in five.

1. Pattern of failure and survival

After median follow-up of 48 months (range, 9 to 174 months), postoperative recurrence was seen in 24 patients, including locoregional and distant recurrence. Locoregional failure (LRF) was seen in 12 patients (11.5%), and distant failure in 13 patients (12.5%) (liver, 7 patients; lung, 4 patients; bone, 1 patient; abdominal wall, 1 patient). One patient had both local and distant failure. Three patients in the LRF group underwent salvage surgery and two patients were cured. Six patients received chemotherapy for LRF and four patients were cured. One patient received salvage radiotherapy, and the remaining two patients refused additional therapy. Three patients with distant metastasis had metastasectomy of the lung or liver. The other patients underwent systemic chemotherapy. Four patients died during chemotherapy because of poor tolerance. Two patients died of cerebral infarction with no evidence of disease recurrence.

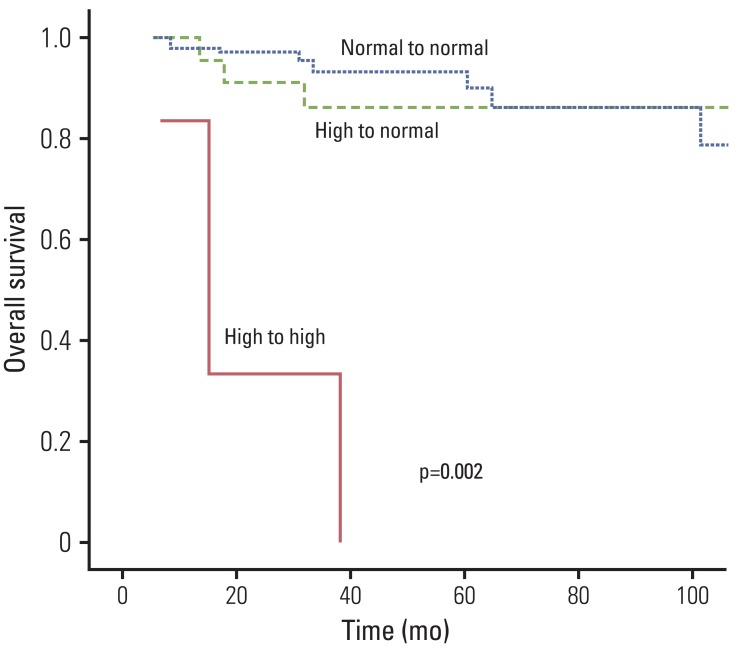

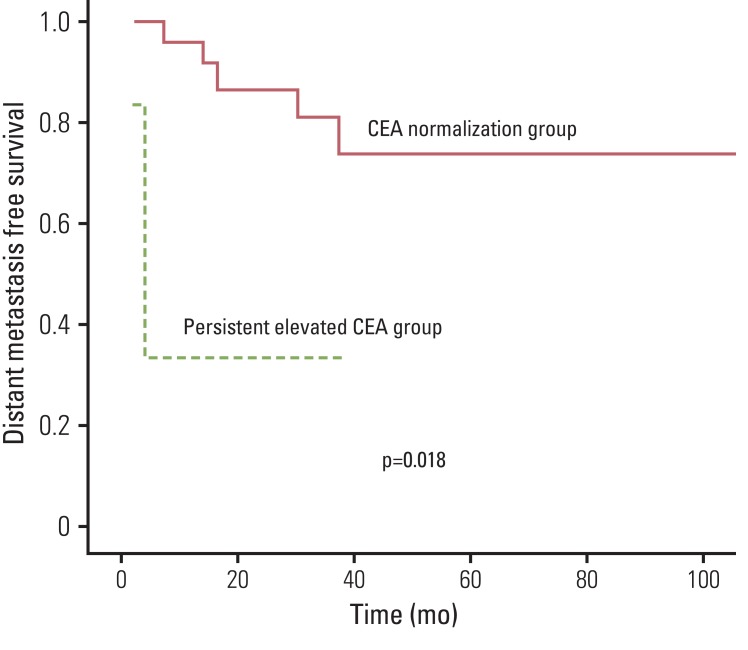

The cumulative five-year DFS was 74.5% and the 5-year OS was 86.4%. On univariate analysis, tumor down staging (p=0.0041), nodal down staging (p=0.036), pathologic T stage (p=0.0147), pathologic N stage (p=0.025), lymphovascular invasion (p=0.031), and perineural invasion (PNI) (p=0.005) were significantly associated with DFS. Pathologic T stage (p=0.017), PNI (p=0.001), resection margin status (p=0.001), initial CEA (p=0.005), and CEA normalization (p<0.001) were significantly associated with OS. Fig. 1 shows the overall survival rate according the CEA level changes. The initial CEA level (p<0.001), CEA normalization after preoperative CRT (p<0.001), and T (p=0.024), and N (p=0.047) down staging were significant prognostic factors for DMFS. The 3-year DMFS was 73.7% in the CEA normalization group, and 33.3% in the persistently elevated CEA level group. This difference was statistically significant (p=0.018) (Fig. 2). In the multivariate analysis, CEA normalization after preoperative CRT (odds ratio [OR], 0.465; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.028 to 0.561), initial CEA (OR, 0.195; 95% CI, 0.017 to 0.382), lymphovascular invasion (OR, 0.975; 95% CI, 0.163 to 0.873), and PNI (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.122 to 0.689) were significantly associated with DFS. PNI (OR, 1.504; 95% CI, 1.621 to 12.502), status of margin (OR, 0.028; 95% CI, 0.002 to 0.337), and CEA normalization (OR, 0.027; 95% CI, 0.009 to 0.149) were predictors of improved OS. CEA normalization (OR, 0.864; 95% CI, 0.11 to 0.281), initial CEA (OR, 1.859; 95% CI, 1.972 to 20.882), and PNI (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.411 to 18.401) were significantly associated with DMFS (Table 3).

2. Adverse events related to treatment

Acute treatment-related toxicities included hematologic, gastrointestinal, dermal, urinary, and hepatic complications. Skin toxicity was the most common: a grade 1 in 39 patients (37.5%) and grade 2 in 15 (14.4%). Two patients experienced grade 4 toxicities (one ileus and one bowel perforation) and required surgery. Five patients (4.8%) suffered with a late developing ileus at a median of 4 months after preoperative CRT, grade 1 in 1 patient, grade 2 in 1 patient, grade 3 in 2 patients, and grade 4 in 1 patient.

Discussion

CEA was first identified from human colon cancer tissue extracts in 1965 by Phil Gold and Samuel O. Freedman. Serum CEA is a glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-cell surface anchored glycoprotein whose specialized sialofucosylated glycoforms serve as functional colon carcinoma L-selectin and E-selectin ligands, which may be critical to the metastatic dissemination of colon carcinoma cells [17]. Thomas et al. [18] reported that serum CEA is expressed in some tumors of epithelial origin including lung cancer, mucinous ovarian carcinoma and colorectal cancer, and sometimes expressed in normal tissue. CEA elevation is associated with several non-neoplastic conditions, including chronic inflammatory disease, renal and hepatic insufficiency, aging, and smoking [19]. Therefore, CEA has a high false positive rate as a screening test for early detection of cancer and should be followed by tests with better specificity.

However, serum CEA levels are useful as a prognostic variable in colorectal cancer patients who had elevated CEA levels at initial diagnosis. Postoperative CEA levels can also be a tool for detection of tumor recurrence [20-23]. In a recent report by Wiratkapun et al. [22], the cumulative DFS of patients with preoperative serum CEA within normal levels was significantly better than that of those whose serum CEA level was 15 ng/mL or more. The study showed a significant correlation between Duke stage and CEA levels. The preoperative CEA levels for Duke A, B, and C stages were 2.4, 4.4, 6.3 ng/mL and patients with distant metastatic recurrence had a significantly higher CEA than those without recurrence. No patient with a CEA level of 1 ng/mL developed metastatic recurrence in this series.

However, the effect of the change in the serum CEA level before and after preoperative CRT on the prognosis of rectal cancer has been evaluated in very few studies. There were two studies that analyzed changes in CEA and its prognostic impact on the survival of rectal cancer [20,21]. Jang et al. [20] found combined pre- and post-CRT CEA levels useful as a prognostic factor for DFS in 109 patients with rectal cancer who had treatment with neoadjuvant CRT and curative resection. They reported that post-CEA≤2.7 ng/mL was an independent predictor of a good response, ypT0 to T2, and ypN0. Kim et al. [21] noted that the reduction in the ratio of pre- to post-CRTs-CEA concentration may be an independent prognostic factor for DFS following preoperative CRT and surgery in rectal cancer patients with an initial serum CEA>6 ng/mL. Serial measurement of a perioperative serum CEA clearance pattern during the preoperative period and in the early and last postoperative periods was also an important indicator for both the OS and DFS rates of patients with stage III rectal cancer with high preoperative CEA levels [24]. In 122 patients with rectal cancer whose serum CEA levels were measured preoperatively and postoperatively on days 7 and 30, the 5-year OS rate of the exponential decrease group was significantly better than the other group. A CEA level of less than 5 ng/mL after preoperative CRT was associated with increased rates of a complete pathologic response. Therefore the postoperative pattern of CEA clearance was a useful prognostic determinant in patients with rectal cancer.

In our study, serum CEA levels were checked before and after CRT. We found DMFS rates similar to rates found in previous studies. Patients with a high CEA level at initial diagnosis showed a lower DMFS rate. Among patients who had an elevated CEA level, those who achieved CEA normalization after preoperative CRT had a better outcome than patients with a persistently elevated CEA level, although our pathologic complete remission (pCR) rates were relatively low (4.8%). The lower pCR rates of our study might result from suboptimal dose to the tumor by conventional radiation technique and the low energy of radiation, 6 MV in most patients. The group with CEA normalization had lower distant metastasis than the group with persistent CEA elevation, and the 5-year DMFS was 73.7% compared with 33.3% (p=0.018). In a subgroup analysis, CEA normalization proved to be a significant factor in DFS (p<0.001) and OS (p<0.001) in pathologic stage I and II rectal cancer. Therefore, close tracking of serum CEA level can be important for predicting good outcomes in stage I and II rectal cancer patients.

Our study had several limitations because of the small sample size and the retrospective analysis. First, the surgery was performed in 104 patients by four colorectal surgeon specialists. Each surgeon has different technical skills for total mesorectal excisions, leading to a higher LRF rate (11.5%) than found in other preoperative CRT studies. Second, the number of lymph nodes retrieved was insufficient. There were 85 patients (81.7%) from whom less than 12 lymph nodes were retrieved [25]. However, patients who underwent preoperative CRT presented with fewer retrieved lymph nodes than those with postoperative CRT. This should be investigated in further studies. Third, we did not include the endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) at the time of initial evaluation. To improve the accuracy of clinical staging, EUS might be augmented with fine needle aspiration of lymph nodes suspicious for metastasis. We can assume that T or N down staging was not significantly associated with OS or DMFS in our multivariate analysis due to the lack of EUS.

Conclusion

Clinical or pathologic stages and initial CEA levels were again confirmed to be prognostic factors for survival in rectal cancer patients in our study. In addition, we observed an effect of the change of serum CEA on the survival. The normalization of CEA levels could provide important information about prognoses in rectal cancer treatment. We need to consider high dose intensity adjuvant chemotherapy for the patients with high CEA level after CRT.

Notes

Conflict of interest relevant to this article was not reported.