Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation in a Surface Antigen-negative and Antibody-positive Patient after Rituximab Plus CHOP Chemotherapy

Article information

Abstract

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that targets B-lymphocytes, and it is widely used to treat non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. However, its use has been implicated in HBV reactivation that's related with the immunosuppressive effects of rituximab. Although the majority of reactivations occur in hepatitis B carriers, a few cases of reactivation have been reported in HBsAg negative patients. However, reactivation in an HBsAg negative/HBsAb positive patient after rituximab treatment has never been reported in Korea. We present here an HBsAg-negative/HBsAb-positive 66-year-old female who displayed reactivation following rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. While she was negative for HBsAg at diagnosis, her viral status was changed at the time of relapse as follows: HBsAg positive, HBsAb negative, HBeAg positive, HBeAb negative and an HBV DNA level of 1165 pg/ml. Our observation suggests that we should monitor for HBV reactivation during rituximab treatment when prior HBV infection or occult infection is suspected, and even in the HBsAg negative/HBsAb positive cases.

INTRODUCTION

It is well known that hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation can occur during chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy. Reactivation usually occurs in hepatitis B carriers who are positive for surface antigen (HBsAg), and this leads to variable manifestations from sub-clinical serum aminotransferase elevation to fatal fulminant hepatitis (1). Therefore, the current recommendations include lamivudine prophylaxis for HBsAg positive patients prior to chemotherapy (2). Since the introduction of rituximab, which is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that targets the B-cells in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, it has been suggested that rituximab treatment might augment the risk of HBV reactivation compared to chemotherapy alone (3). Although the majority of reactivations associated with rituximab have been reported in hepatitis B carriers who are positive for HBsAg, a few cases have been reported in HBsAg negative, anti-hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) positive patients (4-7).

Reactivations in HBsAg negative subjects might be associated with a minute presence of HBV DNA in the blood or liver in the absence of detectable serum HBsAg; this is designated as an occult infection (8). Because the prevalence of occult HBV infection is likely related to the incidence of HBV (9), the prevalence of occult infection in Korean people without HBsAg and normal serum ALT levels has been calculated to be as high as 16% (10). However, reactivation has never been reported in an HBsAg negative/HBsAb positive patient during rituximab treatment in Korea. We report here on a case of reactivation after rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy in an HBsAg negative/HBsAb positive patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old female who was diagnosed in July 2004 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, stage IIB (both tonsils were involved with bilateral cervical neck node enlargement) presented for treatment. She did not have any prior history of diseases such as diabetes, infection, hepatitis etc. The laboratory values on admission, including the complete blood cell counts and the renal function and liver function tests, were within the normal ranges. The results of the liver function tests and the tests for viral markers were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 23 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 22 IU/L, total bilirubin: 0.8 mg/dl, HBsAg negative, HBsAb positive, HBeAg negative, HBeAb positive and anti-HCV negative. She was treated with combination chemotherapy of rituximab plus CHOP (rituximab 375 mg/m2 IV on day 1, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2 IV on day 1, adriamycin 50 mg/m2 IV on day 1, vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 IV on day 1 and prednisone 100 mg PO on days 1~5). Chemotherapy was repeated every three weeks until 8 cycles. She never required a blood transfusion during the treatment period. Her health condition was maintained well and she did not have any concurrent illnesses. Complete remission was achieved after the completion of chemotherapy.

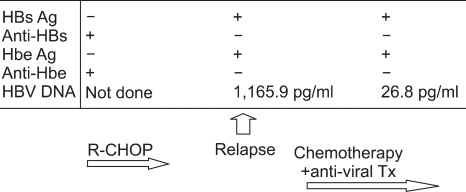

During follow-up, her health remained good, and all the laboratory and radiologic studies, including CT, were normal. However, her left cervical lymph nodes were enlarged in December 2006; CT scan revealed mediastinal and abdominal lymphadenopathy. She was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma relapse, stage IIIB. Salvage chemotherapy with etoposide, solumedrol, cytarabine and cisplatin (ESHAP regimen) was performed; screening blood tests were performed prior to her chemotherapy. However, her viral status had changed: the HBsAg became positive and the HBsAb was negative with normal AST and ALT levels. The HBeAg was also positive and the HBeAb was negative. The serum HBV DNA level was 1,165 pg/ml. Therefore, we maintained giving lamivudine (100 mg per day PO) during treatment. Complete remission was achieved after six cycles of chemotherapy. The serum AST and ALT levels remained within normal range; the serum HBV DNA decreased to 26.8 pg/mL three months after lamivudine treatment (Fig. 1). At present, she is in complete remission without evidence of hepatitis.

The HBs antigen was negative before the rituximab-CHOP chemotherapy. At the time of relapse, a routine screening test revealed the presence of HBs antigen. The HBV DNA titer was increased to 1,165.9 pg/ml, while the liver function test showed normal values. After administering lamibudine, the HBV DNA titer decreased to 26.8 pg/ml. During the salvage chemotherapy, the liver function stayed within the normal range.

DISCUSSION

Chemotherapy-related HBV reactivation is a serious problem for patients with malignant lymphoma as it may cause life-threatening complications such as fulminant hepatic failure. Therefore, prophylactic lamivudine administration has been strongly recommended for hepatitis B carriers who are positive for HBsAg. This anti-viral prophylaxis reduces the incidence of HBV reactivation and morbidity for patients receiving chemotherapy (11). However, there are no clear guidelines for patients with negative HBsAg, even though several cases of fulminant hepatic failure have been reported in HBsAg negative patients (5,6).

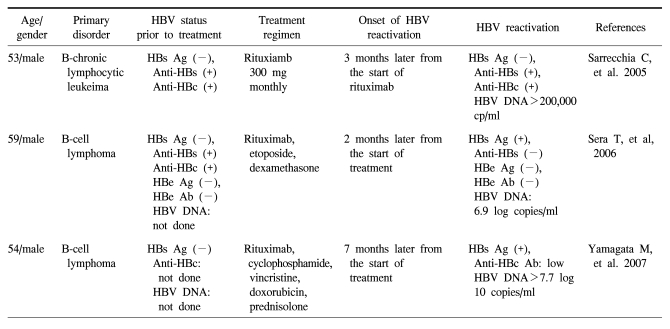

Since the first reported case of HBV reactivation in an HBsAg negative patient who was receiving rituximab [4], there have been several cases of reactivation observed in HBsAg negative, HBsAb positive patients (Table 1). All the cases were regarded as reactivation during or after rituximab-containing chemotherapy because of the evidence for prior HBV infection, such as HBeAb or anti-HBc IgG antibody. All these cases progressed to fulminant hepatic failure that led to death. It has be en shown that HBV replication may persist after resolution of acute hepatitis B. Thus, PCR can detect HBV DNA in the blood or liver of patients with a resolved chronic HBV infection and sustained clearance of HBsAg from their serum (12). Occult infection is defined as serologically undetectable HBsAg despite the presence of HBV DNA in the sera or liver (13), and determining the presence of HBV DNA may depend upon the sensitivity of PCR. Of all the antibodies that can be tested serologically, the presence of IgG anti-HBc and anti-HBe can mean there was a past HBV infection because IgG anti-HBc and anti-HBe are not produced by vaccination. Although occult infection is more common in individuals with serologic evidence of recovery (IgG anti-HBc and anti-HBe positive), it can also be detected in those patients who are HBV seronegative (anti-HBc and anti-HBs negative) (9). A recent study did not find an association between IgG anti-HBc and occult infection (10). Thus, the absence of antibodies indicating prior infection may not exclude occult infection, especially in endemic countries. Although the mechanism and clinical implications of occult infection are unclear, slow or indolent replication may contribute to hepatic inflammation, especially in patients who are receiving chemotherapy.

Summary of the reported cases of HBV reactivation associated with the use of rituximab in surface antigen-negative patients

In this case, the positive anti-HBe findings could suggest a past exposure to HBV. Therefore, in endemic countries, anti-HBe may be more useful in HBsAg negative, HBsAb positive patients to evaluate for a history of immunization or past infection. This could help exclude the presence of occult infection and prevent reactivation during chemotherapy. If the HBeAb is positive, then testing for HBV DNA should be considered. The anti-HBs titer was relatively low (20 mUI/ml) in our case. This could suggest that the protective power of anti-HBs might have been weaker at the time of diagnosis in this case. This was also related with the HBV reactivation during chemotherapy. Therefore, the anti-HBs titer should be measured and then considered prior to chemotherapy, as a patient's immunity may wane with treatment.

In this case, we used rituximab plus CHOP, which is now the standard therapy for B-cell lymphoma. This regimen included rituximab and prednisone, and both increase the risk of HBV reactivation. Rituximab induces B cell suppression, leading to impairment of B-cell immunity. Therefore, rituximab may affect HBV immunity and result in viral replication. However, it is still controversial whether rituximab increases HBV reactivation; a recent review failed to show any significant increase of reactivation associated with rituximab (14). Corticosteroids have immunosuppressive effects and they may also affect reactivation. They could directly stimulate HBV replication via a specific glucocorticoid-response element in the HBV genome (15). Thus, when considering the adverse effects of rituximab plus CHOP and the high probability of long-term survival for patients with malignant lymphoma, adequately monitoring the status of HBV reactivation should be done not only for HBV carriers, but also for those patients who are HBsAg negative.

In conclusion, we report here on a case of reactivation after administering rituximab plus CHOP for treating diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an HBsAg negative, HBsAb positive patient. We suggest that the status of HBV infection should be monitored during and after rituximab treatment, and especially when evidence of prior or occult infection is present, even though the patient shows to be negative for HBsAg and positive for HBsAb. Furthermore, immediate anti-viral treatment should be considered for patients with evidence of HBV reactivation.