Fear of Cancer Recurrence and Its Negative Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life in Long-term Breast Cancer Survivors

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is a common psychological issue in breast cancer (BC) survivors during early survivorship but whether the same is true among long-term survivors has yet to be empirically evaluated. This study investigated FCR level, its associated factors, and impact on quality of life (QoL) in long-term BC survivors.

Materials and Methods

Participants included women diagnosed with BC between 2004 and 2010 at two tertiary hospitals. Survey was conducted in 2020. The study measured FCR with the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory and other patient-reported outcomes, including depression and cancer-related QoL. Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with FCR, and structural equation modeling was conducted to explore the impact of FCR on other outcomes.

Results

Of 333 participants, the mean age at diagnosis was 45.5, and 46% experienced FCR. Age at diagnosis ≤ 45 (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51 to 4.60), shorter time since diagnosis (aOR, 1.75, 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.89), and having a history of recurrence (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.16 to 5.65) was associated with more FCR. FCR was significantly associated with an increased risk of depression (β=0.471, p < 0.001) and negatively impacted emotional functioning (β=−0.531, p < 0.001). In addition, a higher FCR level may impair overall health-related QoL in long-term BC survivors (β=−0.108, p=0.021).

Conclusion

Ten years after diagnosis, long-term BC survivors still experienced a high level of FCR. Further, the negative impact of FCR on QoL and increased depression risk require an FCR screening and appropriate interventions to enhance long-term BC survivors’ QoL.

Introduction

Survival after breast cancer (BC) has improved over the past decades, thanks to advances in diagnosis and targeted treatments. Ninety percent of female BC patients in Korea survive up to 5 years, and more than 80% can survive up to 10 years. This contributed to more than two hundred thousand BC survivors living in Korea at the end of 2017 [1]. The cumulative increase in incident cases and improvement in survival outcomes have contributed to continuous growth in the number of BC survivors. Though most cancer survivors improve their health status and return to everyday life after cancer, evidence suggests that some cancer survivors experience psychological problems such as depression, distress, or anxiety attributable to their fear that cancer might come back. The ongoing fear or concern might negatively impact the patients’ overall health status and physical and social functioning.

In general, fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) is defined as worry that cancer will return or progress in the same or another part of the body [2]. It is one of the most common psychological effects in all cancers. FCR is thought to persist long after the termination of cancer treatment [3]. Also, previous studies have documented that 42%–70% of BC survivors experienced a high FCR level [4], and 21%–40% of them needed help dealing with FCR [5]. However, in most studies, participants were surveyed in the early years of survivorship, during which time the concerns of diagnosis and treatment are probably most intense. Generally, long-term survivors are defined as those who have survived more than 5 years or more since the time of diagnosis [5,6], and their experience of FCR might be differ with those whose treatment are ongoing. However, the prevalence of FCR and other mood disorders in long-term cancer survivors has been much less extensively investigated.

Research on FCR has been predominantly conducted in Western populations, with few studies that have been conducted with Korean cancer survivors [7,8]. Furthermore, Korean long-term BC survivors’ characteristics might differ from those of BC survivors from other countries due to diagnosis at an early age and peaks in the 40- and 50-year age group [9]. Therefore, this study’s findings may help enhance the knowledge of FCR and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in long-term BC survivors diagnosed at an early age. In this study, we targeted long-term BC survivors who have survived on an average of 10 years postdiagnosis, and aimed to assess their FCR level, investigate which factors are associated with FCR, and finally, how FCR impacts other patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

Materials and Methods

1. Participants and data collection

The study’s target population was BC survivors who participated in a cohort study at two tertiary hospitals in Korea: the National Cancer Center (NCC) and Samsung Medical Center (SMC), which started between 2004–2010. Details of baseline recruitment were described elsewhere [10,11]. In 2020, we conducted a long-term follow-up survey to assess the current status of survivors, including FCR, HRQoL, and other PROs.

Nurses at the hospitals contacted potential participants via a phone call and explained the study’s purpose. Next, participants were asked if they agreed to participate in the survey. A few days after phone contact, we sent the participant a greeting letter with a questionnaire and a stamped and addressed return envelope for those who agreed to participate. The participants were asked to complete the questionnaire and return it within 2 weeks.

2. Measures

1) Fear of cancer recurrence

The Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI) was developed and validated in 2009 by Simard and Savard [12]. It has been utilized in many studies to measure the prevalence of FCR and its associated factors. The questionnaire was translated and validated into the Korean language in 2017 and is one of the most common long-form instruments to assess FCR available in the Korean language [8]. The FCRI comprises seven subscales: triggers, severity, psychological distress, coping strategies, functional impairment, insight, and reassurance. Items are responded to using a Likert scale ranging from zero (“not at all” or “never”) to four (“a great deal” or “all the time”). A total score is calculated for each subscale and the total questionnaire by summing the items’ responses. The total score on the FCRI ranges from 0 to 168, where a higher score indicates a higher FCR level. The 9-item Severity subscale of the FCRI can be used to assess the prevalence of FCR and its severity in clinical settings [12]. In this study, a “Severity subscale” score of 13 or higher indicated having FCR based on evidence from previous research [13,14]. The Korean version of the FCRI is considered a reliable instrument to assess FCR in cancer survivors with a reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 [8].

2) Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) with nine items was used to assess depression. The total score is calculated by summing the responses to all items and ranges from 0 to 27.

3) Cancer-related HRQoL

Cancer-related quality of life (QoL) was measured by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (QLQ-C30). This study focused on the Global Health Status subscale and five subscales that assess physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social functioning. Raw scores are transformed to a linear scale ranging from 0 to 100, with a higher score representing a better QoL and higher functioning level. A Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 was translated and validated in 2004 [15].

4) Overall HRQoL

The overall HRQoL was measured using the EuroQol 5-Dimension Questionnaire (EQ-5D). The five dimensions are measured by five items that ask about a participant’s overall health status in the areas of mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and depression/anxiety. The EQ-5D was adapted and validated for use with the Korean population. We applied the weighted quality values for Koreans to calculate the EQ-5D utility index and used it in the final analysis. The EQ-5D utility index score ranges from 0 to 1, and a higher score indicates a better overall HRQoL [16].

5) Sociodemographic and clinical factors

The sociodemographic factors assessed included age, marital status, household income, education level, and employment status. The health-related factors included body mass index, comorbidity status, menopausal status, and pregnancy history. Information on stage at diagnosis, treatment modalities, histological subtype, BC molecular subtype, and cancer recurrence history was obtained from the hospital’s electronic medical records. The diagnosis stage was re-categorized into two levels: stage 0 to II, and stage III to IV. Time since diagnosis ranged from 9 to 16 years and was divided into two groups: > 10 years versus ≤ 10 years.

3. Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics and clinical factors were calculated using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and standard deviations for continuous variables. Statistical significance of differences was tested by Fisher exact test or t test where appropriate. Logistic regression was fitted to identify the factors associated with having FCR (yes/no) status. The univariate and multivariate logistic regression with stepwise selection was performed to identify the final factors associated with FCR after adjustment for other covariates. All measured sociodemographic and clinical factors were considered as covariates in the analysis.

A pathway analysis using the structural equation model (SEM) was performed to evaluate the impact of FCR on HRQoL. The final SEM model included demographic and clinical factors that were statistically significantly with high FCR based on multivariate logistic regression. Bivariate analyses were also conducted to examine the correlation coefficients between FCR and other PROs. The path analysis was then performed by fitting the SEM using the “lavaan” package in R software [17]. The R package “lavaan” was developed in 2011 to provide fully open-source structural equation modeling. The model fit indices were calculated and are reported as recommended [18].

All analyses were conducted using SAS software, ver. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and R software version R ver. 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with a two-sided type I error and an alpha of 0.05.

Results

1. Characteristics of the study population

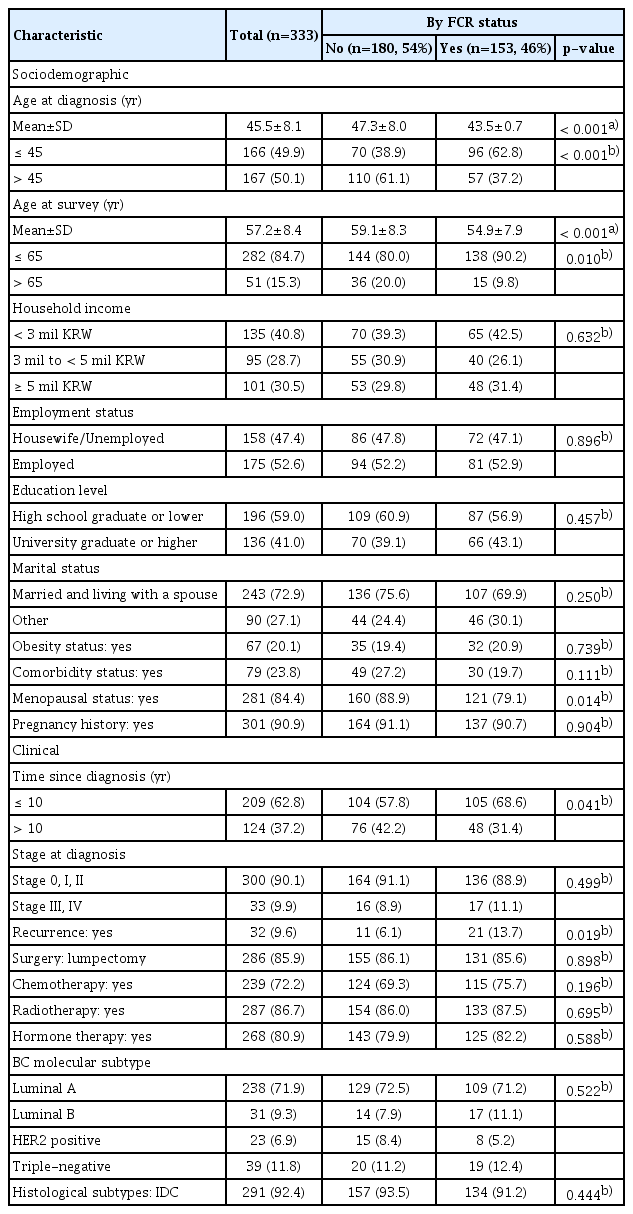

Of the 333 participants in this study, the mean age at diagnosis was 45.5±8.1, and the mean age at the survey was 57.2±8.4 (Table 1). Half of the participants were diagnosed with BC at age 45 or earlier, and 85% of them were age 65 or younger at the survey time. Sixty-three percent of participants had a time since diagnosis ranging from 9 to 10 years, and 37% had a time since diagnosis of more than 10 years. Ninety percent of participants were diagnosed at early stages (0 to II).

Among 333 long-term BC survivors, 153 women (46%) reported having FCR. Those who experienced FCR had a significantly lower age at diagnosis (47.3 vs. 43.5), a lower proportion of having menopause (79% vs. 89%), and a higher proportion having a time since diagnosis of 10 years or less (69% vs. 58%). No difference in other demographic characteristics, including household income level, employment status, education level, and marital status, was observed between the two groups. Among those who experience FCR, 21 participants (14%) had a history of recurrence, which was significantly higher than that among those without experience of FCR (6%). No difference was observed in stage at diagnosis, treatment modalities, and histological subtype between the two groups.

2. FCR scores and other outcomes

Overall, the total FCRI scores ranged from 0 to 142 (over a maximum of 168), with an average of 54.4±25.7 (S1 Table). The mean Trigger and Severity subscales were 12±7 over a maximum of 32 scores. Among the EQ-5D dimensions, 44% of participants reported having problems with pain/discomfort, and 45% reported having problems with anxiety/depression, resulting in an overall EQ-5D index score of 0.918. Regarding depression measures using PHQ-9, 17 (5%) and 53 (16%) participants reported having moderate/severe and mild depression, respectively. All functioning scales assessed by the EORTC QLQ-C30 were approximately 80 or higher.

A significantly lower EQ-5D summary index, higher depression score, and lower functioning scores were reported in those with FCR (Table 2). The overall EQ-5D index score of those with FCR was 0.887±0.088, which was lower compared with 0.945±0.074 reported by those without FCR. Furthermore, a significant difference was observed in the functioning scores between the two groups, with more inferior results in those with FCR: 14.4 scores on the emotional functioning scale, 10.3 scores on the social functioning scale, and 10.1 scores on the role functioning scale (p < 0.001).

3. Factors associated factors with FCR

Results from both univariate (S2 Table) and multivariate logistic analysis (Table 3) showed that younger age at diagnosis (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51 to 4.60), shorter time since diagnosis (aOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.08 to 2.89), and having a history of cancer recurrence (aOR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.16 to 5.65) was significantly associated with having FCR. None of the other sociodemographic and clinical variables were associated with having FCR.

4. Impact of FCR on other PROs from path analysis

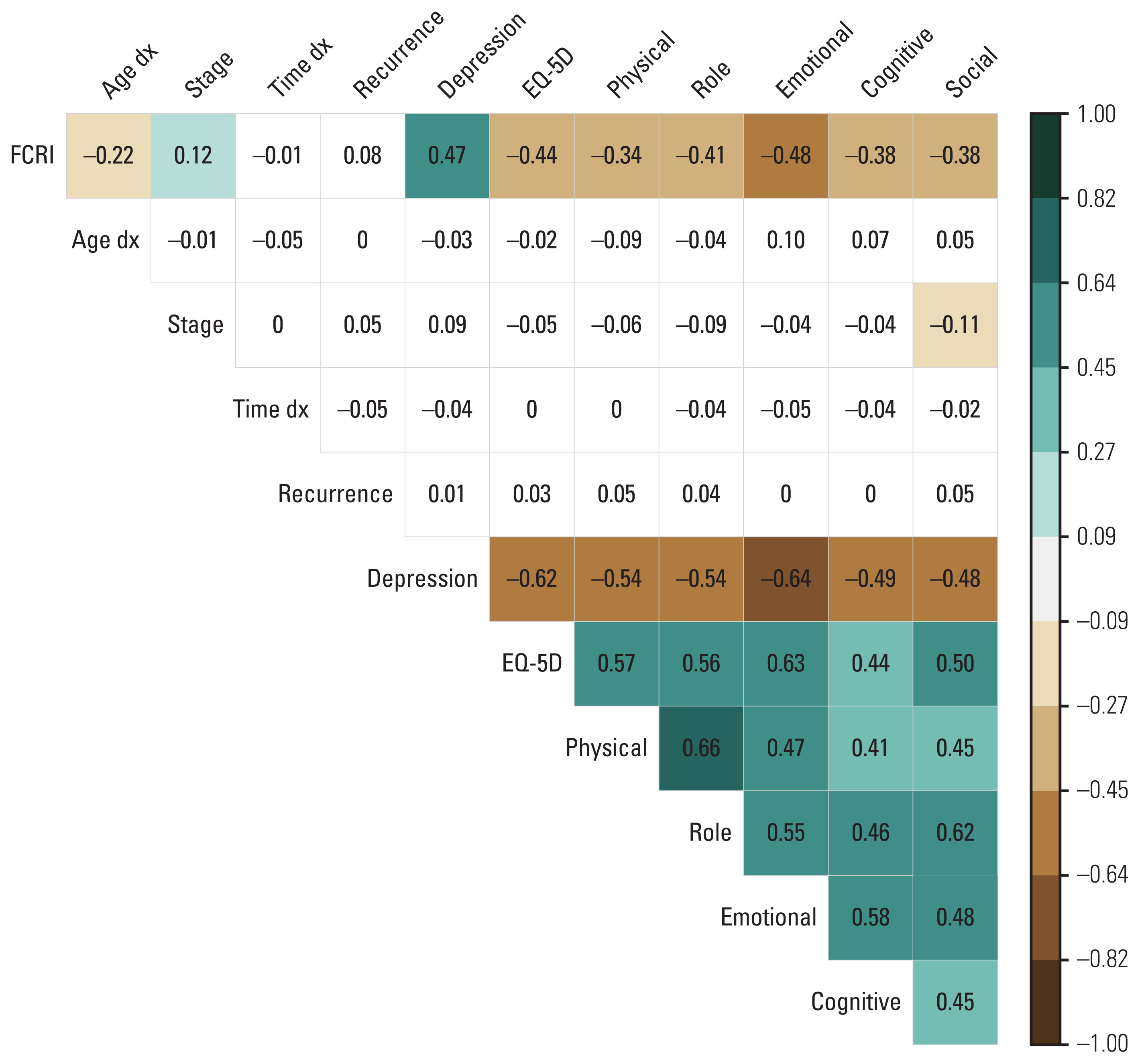

Both the total FCR score and the severity score were significantly correlated with the scores of other PROs (Fig. 1). The total FCRI score had significant negative correlations with overall QoL status (the EQ-5D index), all EORTC QLQ-C30 functioning subscale scores, and a significant positive correlation with depression by PHQ-9 scores.

Correlations between FCRI and other factors. The brown color indicates the statistically significant negative associations. The green color indicates the statistically significant positive associations. The white color indicates non-significant associations. A darker color indicates stronger correlations. EQ-5D, EuroQol 5-Dimension Questionnaire Index; FCRI, Fear of Cancer Inventory; stage, stage at diagnosis; Time dx, time since diagnosis (in year).

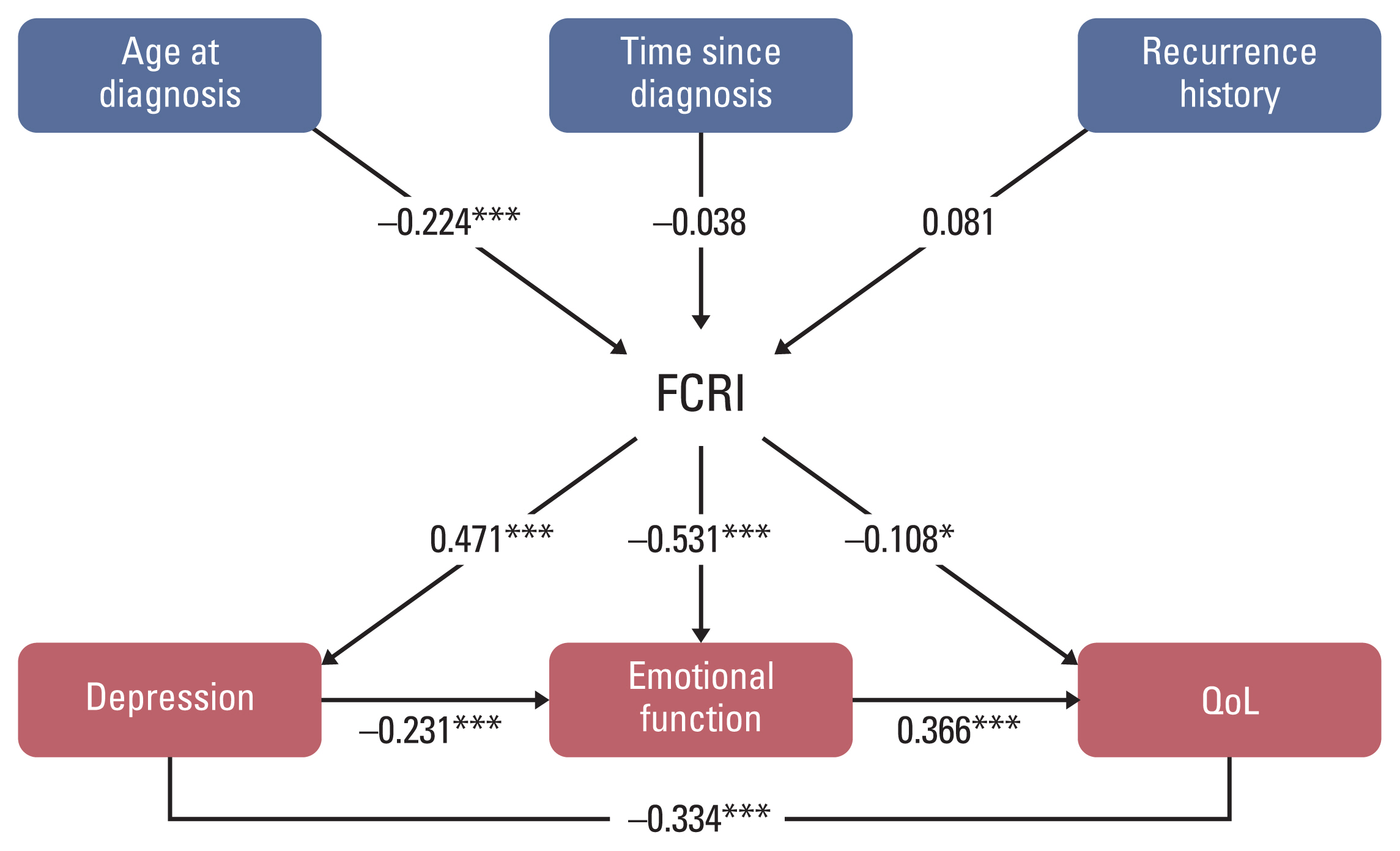

The path analysis showed consistent results that younger age was associated with a higher FCR level (standardized β=−0.224, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2, S3 Table). A higher FCR level had a negative association with emotional function (β=−0.531, p < 0.001) and a positive association with depression (β=0.471, p < 0.001). Furthermore, a higher FCRI score was significantly associated with a lower EQ-5D index score (β=−0.108, p=0.021) which suggests that FCR might impair overall HRQoL in cancer survivors. Depression and emotional functioning were also significantly associated with overall HRQoL (β=−0.334, p < 0.001 and β=0.366, p < 0.001, respectively). The path analysis model had a decent fit with the following indices: Goodness of Fit Index=0.976, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index=0.926, Normed-Fit Index=0.970, Comparative Fit Index=0.986, root mean square error of approximation=0.049, and standardized root mean square residual=0.034 (S4 Table).

Path diagram of the SEM model for the associations between fear of cancer recurrence and other patient-reported outcomes. The structural model presents the effects of age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, history of recurrence, fear of cancer recurrence, and other patient-reported outcomes. FCRI, Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory; QoL, quality of life; SEM, structural equation model. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

The current study targeted long-term young BC survivors with a time since diagnosis ranging from 9 to 16 years, and the study population were those diagnosed with BC at an early age (an average of 45 years). Even though FCR persists long after treatment completion [3], most previous studies assessed FCR in the early course of treatment or survivorship [4,5], and few have focused on FCR among long-term survivors, especially those 10 years or more postdiagnosis. Cancer survivors who have survived more than 5 years or more since the time of diagnosis are considered as long-term survivors [5,6]. In this study, the mean and median survival time of the participants were 11.6 years and 10 years respectively, and thus, they can be considered long-term BC survivors. These are the unique characteristics that differentiate our findings from previous work. Given the increasing number of long-term BC survivors and the limited knowledge on psychological issues in young BC survivors, findings from the current study might help provide the information needed to develop support programs for this particular population.

A low FCR level can be considered a normal reaction of survivors to cancer progression, encouraging survivors to adopt better health behaviors. However, when fear becomes clinically significant or problematic, survivors have chronic intrusive thoughts about a possible recurrence, which might increase depression risk and deteriorate their QoL. Even though 10 years had passed since the initial diagnosis, our results prove that BC survivors still had concerns and worries about their cancer disease. Approximately half of the participants had FCR, consistent with previous studies that reported an FCR prevalence of 40% to 60% [19–21]. In addition, the FCRI subscale scores and total FCRI score reported by our participants were relatively similar to previous studies despite the difference in time since cancer diagnosis [7,14]. In this study, 10% of the participants had a history of recurrence, and these women had a 2.5-fold higher risk of experiencing FCR than those without recurrence. Thus, our findings suggest that long-term BC survivors with a history of FCR might need support to reduce their FCR, and future research on a larger sample of this particular population is needed to provide more comprehensive findings.

Consistent with our research, other studies [4,22,23] found that younger cancer survivors experienced more FCR. For example, a study reported that more than 60% of young cancer survivors had clinical FCR [24]. A more aggressive tumor subtype, and worse prognosis [25] may explain why BC patients diagnosed at a younger age had more concerns and more fears about their disease’s progress. Thus, accumulated evidence supports that early age at diagnosis is a robust predictor for higher FCR. In terms of clinical factors, previous studies found a shorter time since diagnosis [22,24] and worse disease prognosis, such as having a previous recurrence or advanced stage, were associated with higher FCR levels [24,26]. Again, these findings were consistent with our study. However, it should be noted that the time since diagnosis was longer in the present study, with a minimum of 9 years, whereas other studies were commonly conducted among survivors with less than 5 years since diagnosis.

Cancer survivors are at an elevated risk for psychological issues such as FCR, distress, anxiety, and depression that might persist years after receiving treatment. For example, according to previous studies, a higher FCR level was strongly associated with higher levels of depression [2,12,27], emotional distress [7,22,24], and anxiety [27,28]. Consequently, having FCR might worsen cancer survivors’ overall QoL [14,28], which was consistent with our findings.

When fear or concern about cancer recurrence becomes problematic, screening and management for FCR are crucial. Cancer survivors with a high FCR level might benefit from psychoeducation programs or other psychological interventions such as attention training, metacognitive therapy, acceptance, or mindfulness [29,30]. The increasing number of clinical trials to develop therapies to reduce FCR in recent years indicates that FCR is one of the common unmet needs among cancer survivors, and healthcare providers are trying to help survivors with these psychological issues. However, most of the interventions were conducted in Western countries. Thus far, no research on interventions to reduce FCR among Korean cancer survivors and especially long-term cancer survivors has been conducted.

Our study had several limitations. First, due to the nature of cross-sectional data, we could not assess variation in FCR over time and likewise cannot determine causal relationships between FCR and other PROs measured in our research. Second, our results should be interpreted with caution because 90% of the study participants were in BC stage 0 to II, with nine years as the minimum time since diagnosis. In addition, this study might have selection bias due to the fact that only participants agreed to participate were included in the analysis. Thus, they would generally have better HRQoL than advanced stage-patients or those who rejected to participate in the survey.

After 5 years of adjuvant endocrine therapy, BC survivors remain at risk for cancer recurrence. The most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network Survivorship Guidelines recommend that psychological issues, including FCR, are among the eight most common issues that should be managed in cancer survivors [31]. Long-term BC survivors in our study, especially those diagnosed at a younger age and had recurrence history, still expressed fear or concerns about cancer, which deteriorates their overall QoL and increases depression risk. Thus, long-term BC survivors who experience these psychological issues should be identified and supported.

Though BC survivors often experience worries and uncertainties about their disease, not many directly express these feelings to healthcare providers. Therefore, doctors and other healthcare providers should identify emotional distress in BC survivors and provide appropriate intervention. We believe that our research findings are of interest to healthcare providers and BC survivors because it provides a better understanding of FCR and its impact on long-term BC survivors. Future research should focus on developing screening and psychological interventions to reduce FCR for this growing survivor population, especially in Asian BC survivors.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at Cancer Research and Treatment website (https://www.e-crt.org).

Notes

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the National Cancer Center institutional review board (IRB approval number: NCC2019-0281). All participants gave their consent to participate by signing an informed consent form.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the analysis: Tran TXM, Jung SY, Lee EG, Kim NY, Kang D, Cho J, Lee E, Chang YJ, Cho H (Hyunsoon Cho).

Collected the data: Tran TXM, Cho H (Heeyoun Cho), Kim NY, Shim S, Kim HY, Chang YJ.

Contributed data or analysis tools: Tran TXM, Jung S, Lee EG, Kang D, Cho J, Lee E, Chang YJ, Cho H (Hyunsoon Cho).

Performed the analysis: Tran TXM, Cho H (Hyunsoon Cho).

Wrote the paper: Tran TXM, Jung SY, Lee EG, Cho H (Heeyoun Cho), Kim NY, Shim S, Kim HY, Kang D, Cho J, Lee E, Chang YJ, Cho H (Hyunsoon Cho).

Conflicts of Interest

Conflict of interest relevant to this article was not reported.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Cancer Center of Korea (grant numbers NCC-04101502 and NCC-1911271). The funder had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.