AbstractAccurate prediction of impending death (i.e., last few days of life) is essential for terminally-ill cancer patients and their families. International guidelines state that clinicians should identify patients with impending death, communicate the prognosis with patients and families, help them with their end-of-life decision-making, and provide sufficient symptom palliation. Over the past decade, several national and international studies have been conducted that systematically investigated signs and symptoms of impending death as well as how to communicate such a prognosis effectively with patients and families. In this article, we summarize the current evidence on prognostication and communication regarding the last days of life of patients with cancer, and future directions of clinical research.

IntroductionAccurate prediction of impending death (i.e., last few days of life) is essential for terminally-ill cancer patients [1,2]. It can help patients, families, and clinicians clarify goals of care, promote shared decision-making, avoid unnecessary investigations and aggressive care, ensure goal-concordant care, and allow patients and families to complete unfinished business and achieve a good death [1–4]. International guidelines state that clinicians should identify patients with impending death, communicate the prognosis with patients and families, help them with their end-of-life (EOL) decision-making, and provide sufficient symptom palliation [1]. Over the past decade, several national and international studies have been conducted that systematically investigated signs and symptoms of impending death as well as how to communicate such a prognosis effectively with patients and families [5–15]. In this article, we review important findings on prognostication and communication regarding the last days of life of patients with cancer.

Prognostication of Impending Death1. General considerationOne of the early studies was a prospective observational study at a palliative care unit (PCU). Morita et al. [16] revealed that the proportion of patients with decreased consciousness increased over the last week of life, and that the median time from the onset of death rattle, respiration with mandibular movement (RMM), peripheral cyanosis, and pulselessness of the radial artery to death was 23, 2.5, 1.0, and 1.0 hours respectively. In 2013, an international Delphi study provided expert consensus on various categories for prediction of the last hours or days of life, such as changes related to “breathing”, “skin”, and “consciousness/cognition” [5].

2. Clinician prediction of survivalClinician prediction of survival (CPS) is an easy and quick way of prognostication. CPS has three question formats: temporal, probabilistic, and surprise questions [17]. With the temporal approach, a clinician is asked, “How long will this patient live?” The answer is provided as a specific time frame such as “3 days.” This is the most common approach for prognostication in daily practice. The accuracy of temporal approach is traditionally defined as a predicted survival rate of within ±33% of actual survival [18–21]. This approach often results in overestimation and has a 20% to 30% rate of accuracy, even among palliative care specialists [19].

With the probabilistic approach, a clinician is asked, “What is the approximate probability that this patient will be alive (0%–100%)?” An estimation of the probability of survival is considered to be accurate if either the patient died and the clinician endorsed a survival probability ≤ 30%, or the patient survived and the clinician selected a survival probability ≥ 70% [19].

Previous studies involving advanced cancer patients admitted to acute PCUs (median survival, 8 to 14 days) showed that 24-hour and 48-hour probabilistic CPS was consistently more accurate than temporal CPS [19,22]. In addition, while nurses were not more accurate than physicians in estimating survival using temporal CPS, they were largely more accurate than physicians in estimating survival using 24-hour and 48-hour probabilistic CPS [19,22].

With respect to changes in accuracy over time, Selby et al. [23] explored the accuracy of temporal CPS using time-based prognostic categories, and found that CPS of < 24 hours and one to 7 days were significantly more likely to be accurate than CPS of longer intervals. Hui et al. [24] investigated the accuracy of temporal CPS with time-based categories (0–14 days, 15–42 days, and ≥ 43 days), and reported that CPS was as accurate as prognostic tools such as Palliative Prognostic (PaP) Score and Palliative Prognostic Index among advanced cancer patients with a median overall survival of 10 days. Focusing on the last 2 weeks of life, Perez-Cruz et al. [22] showed that while the accuracy of temporal CPS was relatively stable over time, that of 24-hour and 48-hour probabilistic CPS significantly decreased as patients approached death.

A surprise question (SQ), “would I be surprised if this patient died in [specific timeframe]?”, is a simple and feasible screening tool to identify patients at their EOL [25,26]. In addition to SQ estimating 1-year mortality, those of various other timeframes have been proposed (e.g., 30, 7, 3, and 1 day(s)) [12,25–27]. In secondary analyses of the East-Asian cross-cultural collaborative Study to Elucidate the Dying process (EASED) study, Ikari et al. [12,28] showed that among 1,411 advanced cancer patients with Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) ≤ 20, the sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) of 3-day SQ were 94.3% and 83.6%, respectively, and those of 1-day SQ were 82.0% and 91.0%, respectively. These findings indicate that both 3-day and 1-day SQs can be useful screening tools to identify patients facing impending death. In another study, Kim et al. [29] examined the accuracy of 7-day SQ in 130 patients admitted to PCUs in South Korea, and reported a sensitivity of 47%, specificity of 89%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 35%, and NPV of 93%, with an overall accuracy of 84% (C-index 0.66).

3. Physical signsIn the 2010s, two multicenter, prospective, observational studies were conducted to investigate the dying process. The first was the Investigating the Process of Dying (IPOD) study that enrolled 357 consecutive patients with advanced cancer who were admitted to two acute palliative care units (APCUs) in the United States and Brazil [6,7]. The IPOD study systematically examined the diagnostic performance of comprehensive signs and symptoms for the prediction of death within 3 days. The authors identified “early signs” and “late signs” of impending death (Table 1). The early signs (i.e., decreased level of consciousness, PPS ≤ 20%, and dysphagia of liquids) appeared at a high frequency and more than 3 days before death, and showed a low specificity and positive likelihood ratio (LR) for impending death. In contrast, late signs occurred mostly in the last 3 days of life and at a lower frequency, but showed a very high specificity and positive LR for death within 3 days.

The other study was EASED, an East-Asian, multicenter cohort study conducted at PCUs in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. One of its correlative studies used Japanese data from 22 sites, and investigated the diagnostic performance of 15 clinical signs after patients’ performance status had declined to PPS ≤ 20% (n=1,396) [11]. The authors confirmed that the physical signs were divided into early and late signs, consistent with the findings of the IPOD study (Table 1).

4. Vital signsAlthough vital signs in patients with advanced cancer can vary over time and may fluctuate due to acute complications, they show some characteristic changes in the last days of life. The IPOD study showed that, overall, blood pressure and oxygen saturation gradually decrease, body temperature increases, and heart rate and respiratory rate remain mostly constant, during the last 3 days of life [10]. Several prognostic tools for impending death include vital signs, such as Objective Palliative Prognostic Score (OPPS) [30], Prognosis in Palliative care Study predictor (PiPS) models [31], and Objective Prognostic Index for advanced cancer (OPI-AC) [32], all of which include heart rate as a variable in the prediction of days of survival. However, as a large proportion of patients have normal vital signs in the last days of life (40% to 80% of patients during the last 3 days of life), vital signs alone should not be overly relied on in the prediction of impending death [10]. Rather, they can be deemed supplemental to other signs of impending death for predicting death within the next 3 days. In practice, marked deterioration of vital signs often occurs in the last minutes/hours of life and may serve as a predictor of death within the same day.

5. Physiological parametersSeveral laboratory abnormalities have been shown to indicate poor survival. For example, leukocytosis, neutrophilia, low lymphocyte percentage, thrombocytopenia, hyperkalemia, elevated urea, creatinine, alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, lactic dehydrogenase, total bilirubin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and hypoalbuminemia are in part included in several prognostic tools which can identify patients with days of survival, such as PaP Score, Objective Prognostic Scale (OPS), OPPS, PiPS model, and OPI-AC [30–34]. Recently, Nagasako et al. [35] reported that Glasgow Prognostic Score indicating elevated CRP and hypoalbuminemia optimized with concomitant thrombocytopenia was significantly correlated with 3-day mortality, and had a specificity of 97.5% and high positive LR > 5.

Among objective and physiological measures with a prognostic value is the phase angle, a marker of cellular membrane integrity and hydration. The phase angle is measured by bioelectric impedance analysis. It typically ranges from 4 to 9 in healthy individuals, and is known to be lower in patients with shorter survival [36–38]. A prospective study involving 204 APCU patients with advanced cancer and a median survival of 10 days revealed that the phase angle was not significantly correlated with survival in the entire group, but remained a significant prognostic factor in a non-edematous subgroup [39]. Specifically, a phase angle ≤ 3° had a sensitivity of 50%, specificity of 90%, and overall accuracy of 86% (95% confidence interval, 77% to 93%) for 3-day survival in patients without edema. Further studies are needed to validate these findings.

6. SymptomsPatients with advanced cancer suffer from multiple symptoms throughout the disease trajectory. Acute complications in the last weeks to days of life may contribute to an increased symptom burden [40]. Indeed, the intensity of certain symptoms, such as fatigue, anorexia, drowsiness, and dyspnea, often worsens in the last weeks to days of life [41]. The EASED study indicated that patients whose symptoms (i.e., dyspnea, fatigue, dry mouth, and drowsiness) worsened during the first week of admission to PCUs had shorter survival (median survival, 15 to 21 days) than those whose symptoms improved (median survival, 23 to 31 days) or remained stable (median survival, 27 to 29 days) (p < 0.001) [42].

The IPOD study demonstrated that certain symptoms (e.g., anorexia, drowsiness, fatigue, dyspnea, and insomnia) continued to worsen over the last week of life, even under specialist palliative care [8]. Indeed, fatigue (or poor performance status), anorexia, dyspnea, and/or delirium are incorporated in various prognostic scales, and their presence indicates a poorer prognosis [31,33,43].

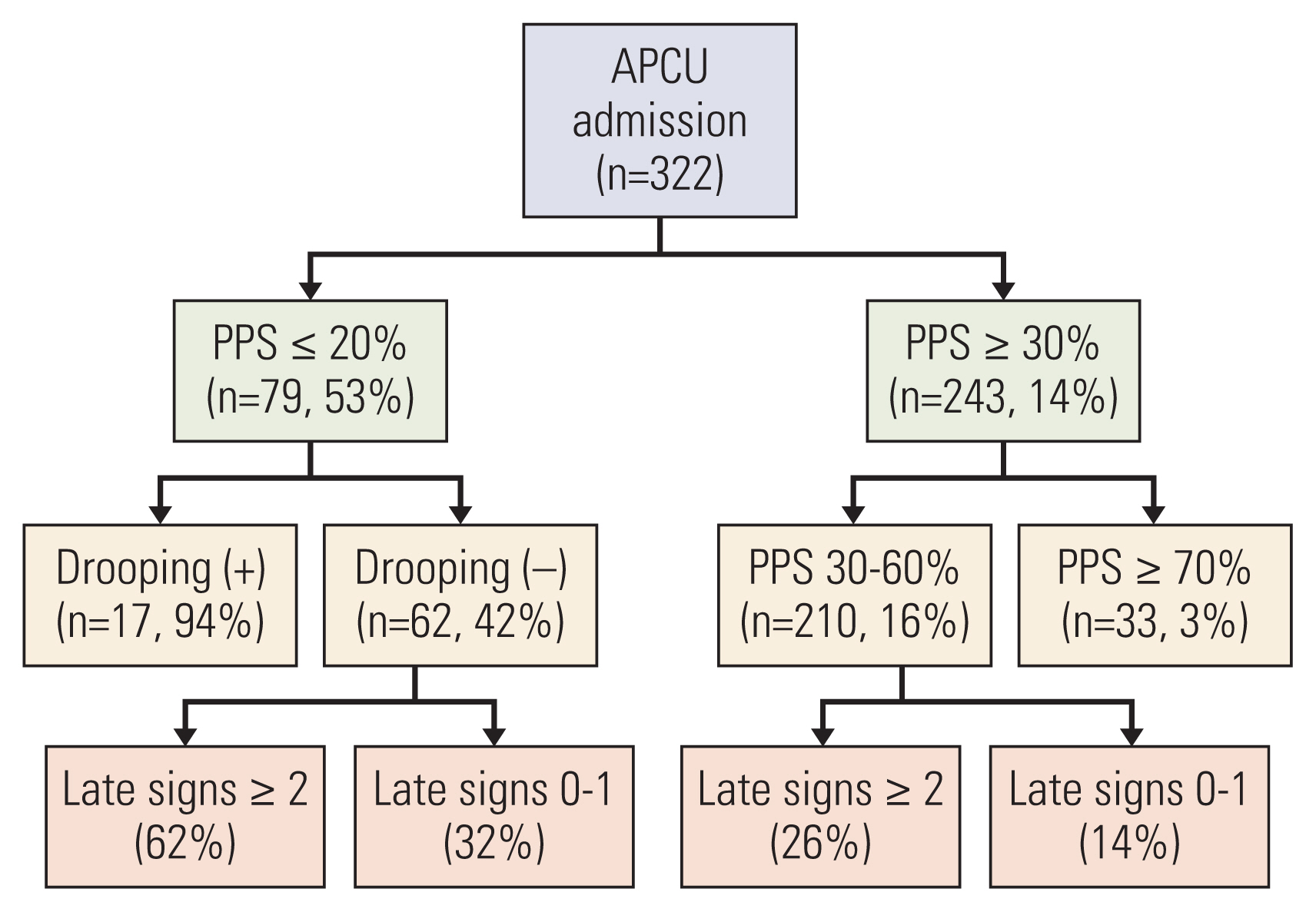

7. Diagnostic models(1) First diagnostic model: the IPOD modelHui et al. [44] proposed a diagnostic model consisting of two signs (PPS and drooping of nasolabial folds) to predict death within 3 days by utilizing recursive partitioning analysis (Fig. 1). The 3-day mortality rates of patients with PPS ≤ 20% and drooping of nasolabial folds present, PPS ≤ 20% and drooping of nasolabial folds absent, PPS of 30 to 60%, and PPS ≥ 70% were 94, 42, 16, and 3%, respectively (accuracy, 81%).

(2) Second diagnostic model: the prediction of 3-day impending death-decision tree (P3did-DT)The prediction of impending death becomes especially relevant and important for patients who are considered close to death based on clinical signs, such as decreased activities and oral intake [6]. Although accurate prediction of impending death among patients who started to show such “early signs” remains challenging, it would help clinicians urgently expedite EOL decision-making [6]. Using Japanese data of the EASED study, Mori et al. [11] proposed another diagnostic model to predict death within 3 days by utilizing recursive partitioning analysis (prediction of 3-day impending death-decision tree [P3did-DT]) (Fig. 2). P3did-DT was based on three variables and had four terminal leaves: urinary output (u/o) ≤ 200 mL/day and decreased response to verbal stimuli, u/o ≤ 200 mL/day and no decreased response to verbal stimuli, u/o > 200 mL/day and Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) ≤ −2, and u/o > 200 mL/day and RASS ≥ −1. The 3-day mortality rates were 80.3%, 53.3%, 39.9%, and 20.6%, respectively (accuracy, 68.3%).

(3) A system-based prediction score: the P3did-scoreIn addition to P3did-DT, EASED investigators developed P3did-score by categorizing 10 representative signs into four systems: nervous (decreased level of consciousness as indicated by RASS ≤ −2), cardiovascular (peripheral cyanosis, pulselessness of radial artery, and decreased u/o), respiratory (apnea, Cheyne-Stokes breathing, and RMM), and musculoskeletal (inability to close eyelids, hyperextension of the neck, and drooping of nasolabial folds) systems. If any sign was present within each system, a score of 1 was given to the system without a weight being assigned (i.e., each system would have a score of 0 or 1). The total score was calculated by adding the score of each system, which ranges from 0 to 4 with a higher score indicating the presence of clinical signs in more systems (P3did-score) (Table 2). Overall, 79.6, 62.9, 47.2, 32.8, and 17.4% of patients with P3did-scores of 4, 3, 2, 1, and 0, respectively, died within 3 days [11].

Of note, P3did-DT and P3did-score were derived from patients with PPS ≤ 20%, while the IPOD model was derived from unselected PCU patients, which may explain their different performance. All these models require external validation.

8. Sudden unexpected deathAlthough a majority of patients with advanced cancer show a gradual and predictable functional decline through a terminal phase to death, a small proportion in the palliative care setting may die suddenly and/or unexpectedly [45]. So far, four major definitions of sudden unexpected death have been utilized in the palliative care literature: rapid decline death (i.e., a sudden death preceded by functional decline over 1–2 days) [46], surprise death (i.e., the primary responsible physicians answered “yes” to the question, “Were you surprised by the timing of death?”) [9], unexpected death (i.e., a death that occurred earlier than the physician had anticipated) [9], and performance status–defined sudden death (i.e., a death that occurred within 1 week of functional status assessment with an Australia-modified Karnofsky performance status ≥ 50) [47]. Using these four definitions, Ito et al. [13] prospectively followed 1,896 PCU patients, and found that the incidence of rapid decline death was the highest (30-day cumulative incidence: 16.8%), followed by surprise death (9.6%), unexpected death (9.0%) [46,48], and performance status–defined sudden death (6.4%) [13]. These findings were generally consistent with the IPOD study, which found that approximately 10% of PCU deaths were unexpected by physicians and nurses based on the “surprise” and “unexpected death” questions [9]. In EOL discussions and decision-making, clinicians should bear in mind that approximately 1 to 2 in 10 patients might experience unexpected deterioration and death.

Communication of Impending Death1. Communication with patientsEffective communication with patients, shared decision-making, and family involvement are among the essential elements of quality EOL care [49,50]. The NICE guideline on the care of adults in the last days of life also recommends that clinicians disclose the impending death to patients, clarify goals of care, and facilitate EOL decision-making [1]. However, these are challenging, as most cancer patients become uncommunicative due to the development of delirium and acute complications, medications with sedative effects, and/or the natural dying process [8,51–55].

In addition, whether to disclose the nature of impending death to patients varies widely across cultures. In Asia, for example, non/partial-disclosure and family-centered decision-making remain the cultural norm [56–62]. In the EASED study analyzing data of 2,138 advanced cancer patients admitted to PCUs and deceased during the hospitalization, Yamaguchi et al. [14] reported that markedly fewer Japanese (4.8%) and South Korean (19.6%) patients were informed of their impending death, whereas 66.4% of Taiwanese were informed. In contrast, over 90% of families were informed of their loved one’s impending death in all three countries, indicating a varying degree of family-centered EOL decision-making in East Asia. Thus, it is vital to establish the communication needs of each patient before prognostic disclosure, and explore whether the patient has any cultural, religious, social, or spiritual preferences for shared decision-making [1,61].

2. Communication with familiesDuring patients’ last days of life, it is essential to help families prepare for their loved one’s death cognitively, emotionally, and practically, so that they can make any necessary arrangements. Studies involving bereaved families of cancer patients have indicated the need for improved communication with families of imminently dying patients. A bereaved family survey involving 22 hospitals in seven European and South American countries showed that although 87% of families were told of their relative’s dying, only 63% were informed about what to expect during the dying phase [63]. A bereaved family survey in Japan also revealed that nearly a third of bereaved families perceived some need to improve clinicians’ explanation about impending death [15]. Determinants of the family-perceived need for improvements in the explanation included the following: not receiving an explicit explanation about physical signs of impending death; not receiving an explanation of how long the patient and family could talk; receiving an excessive warning of impending death; and having a feeling of uncertainty caused by vague explanations about future changes.

When explaining signs of impending death to families, caution needs to be taken as family caregivers may perceive some signs as distressing to patients. For example, in a cross-sectional survey of bereaved families of cancer patients in 95 PCUs, up to two-thirds of families reported high distress levels related to death rattle, and higher distress levels were associated with unawareness about death rattle being a natural phenomenon and their fear and distressing interpretations of death rattle [64]. In another study to explore appropriate physicians’ behaviors on death pronouncement, compassion-enhanced behaviors which included reassuring families that the patient did not experience pain associated with RMM resulted in higher physician compassion scores, greater trust in a physician, and less negative emotions among families [65].

Lack of timely explanation about impending death could leave families unprepared for their loved one’s death, resulting in a sense of having unfinished business. Even among families of cancer patients who spent the last days of life in PCUs, over a quarter reported some unfinished business [66]. Moreover, families with unfinished business had significantly higher depression and grief scores after bereavement compared with those without it. Furthermore, even if families do not explicitly talk about death with their loved one, they could act in preparation for their loved one’s death. A bereaved family survey showed that the majority of families acted in such a way, and those who acted more were less likely to suffer depression and complicated grief [67].

While uncertainty is unavoidable in prognostication [17], addressing it compassionately and discussing what can be done may help most patients and families maintain hope [68]. The goals of prognostic discussions include improving illness understanding, promoting prognostic awareness towards acceptance, and ultimately decision-making [69]. There are many different frameworks for approaching these sensitive discussions, and they typically involve finding the right time and setting for the discussion, exploring patients/families’ understanding, acknowledging the uncertainty, communicating information in a clear, honest, empathic manner, responding to emotions, and providing follow-up [70]. Based on the aforementioned literature and anecdotal evidence, we propose several specific strategies when discussing impending death with patients and families (Table 3).

Clinical Implications of PrognosticationUpon the recognition that a patient may be in the last days of life, and before he or she loses communication capacity, clinicians need to adopt an urgent and effective interdisciplinary approach to clarify goals of care, ensure compassionate communication and shared decision-making, address any unfinished business, and support their last wishes.

Predictors of impending death to focus on when informing of impending death may depend on the needs of patients, families, and clinicians. For example, when an inpatient’s family wants to know if they can safely leave the room for one night to rest at home and return the next day to accompany the patient again, the absence of signs of impending death and/or tools with high sensitivity and NPV would be helpful (e.g., 1-day SQ, P3did-score of 0). In contrast, if a patient and/or family wants to spend the last hours to days of life in a private room, or if clinicians consider softening visit restrictions in the COVID-19 pandemic, and wish to know when death is absolutely imminent, identifying late signs with high specificity and PPV would be informative.

Recognition of impending death may also prompt clinicians to reconsider if the current symptom management is in line with the patient’s individual goals. Individuals have their own preferences toward the balance between symptom relief and maintenance of communication capacity in the last days of life [71]. Thus, while managing severe distress such as dyspnea, agitation, and refractory suffering, clinicians should bear in mind the uniqueness of patients’ preferences when titrating medications with sedative effects (e.g., opioids, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines) [52,53,72–75].

Lastly, signs of impending death represent the last chance for both patients and families to complete unfinished business and share their appreciation, forgiveness, and good-byes (i.e., “last words”). Clinicians can help patients and/or families understand the situation, arrange the environment appropriately (e.g., transfer to a private room, softening of visit restrictions), and help them share their words and feelings with each other either explicitly or implicitly when appropriate [76]. The recognition and compassionate communication of impending death, and effective approach may help provide truly value-based, goal-concordant care in the last days of life.

Future DirectionsDespite the increasing number of studies on impending death, a number of unanswered questions remain. Among the most important questions in the prognostication of impending death is “why should we prognosticate?”. Table 4 summarizes unanswered questions and future directions in prognostication of impending death. Future studies should help clinicians better prognosticate impending death, effectively communicate with patients and families, and improve clinically important outcomes.

ConclusionVarious signs, symptoms, and tools have been reported for use to predict the impending death of advanced cancer patients. Future efforts should be made to clarify aims of prognostication, establish diagnostic performance of various tools, and develop individualized communication strategies as well as appropriate outcome measurements. Ultimately, impact studies should be conducted to confirm that accurate prognostication and effective communication can actually improve clinically important outcomes of patients and families in the last days of life.

NotesAuthor Contributions Conceived and designed the analysis: Mori M, Morita T, Bruera E, Hui D. Collected the data: Mori M, Hui D. Contributed data or analysis tools: Mori M, Morita T, Bruera E, Hui D. Wrote the paper: Mori M, Morita T, Bruera E, Hui D. Final approval: Mori M, Morita T, Bruera E, Hui D. AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank all the IPOD and EASED investigators. We appreciate Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Hospice Palliative Care Foundation and JSPS KAKENHI (JP16K15418, 18H02736). DH was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA214960; R01CA225701; R01CA231471).

Fig. 1A diagnostic model for impending death based on the IPOD study. Late signs included in this recursive partitioning model were: death rattle, respiration with mandibular movement, peripheral cyanosis, Cheyne-Stokes breathing, pulselessness of radial artery, decreased response to verbal stimuli, decreased response to visual stimuli, nonreactive pupils, drooping of nasolabial fold, hyperextension of neck, inability to close eyelids, grunting of vocal cords, and upper gastrointestinal bleed. APCU, acute palliative care unit; IPOD, Investigating the Process of Dying; PPS, Palliative Performance Scale. Reference: Hui et al. Cancer. 2015;121:3914-21 [44].

Fig. 2A diagnostic model for impending death among patients with PPS ≤ 20% based on the EASED study (P3did-DT). A recursive partitioning model for impending death within 3 days in cancer patients who developed PPS ≤ 20% during admission at palliative care units. The entire dataset of 15 clinical signs of 1,396 patients were used for analyses. Clinical signs included in this model were: decreased level of consciousness (RASS ≤ −2), dysphagia of liquids, death rattle, respiration with mandibular movement, peripheral cyanosis, Cheyne-Stokes breathing, pulselessness of radial artery, decreased response to verbal stimuli, decreased response to visual stimuli, apnea periods, drooping of nasolabial fold, hyperextension of neck, inability to close eyelids, grunting of vocal cords, and decreased urine output. EASED, East-Asian cross-cultural collaborative Study to Elucidate the Dying process; P3did-DT, prediction of 3-day impending death-decision tree; PPS, Palliative Performance Scale; RASS, Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale. Reference: Mori et al. Cancer Med. 2021;10:7988-95 [11].

Table 1Frequency and diagnostic performance of impending death signs at different timing and settings

CI, confidence interval; EASED, East-Asian cross-cultural collaborative Study to Elucidate the Dying process; IPOD, Investigating the Process of Dying; LR, likelihood ratio; PPS, Palliative Performance Scale; RASS, Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale. b) Any occurrence of the sign of interest within the last 3 days of life among patients with PPS ≤ 20% and who died in the palliative care units, d) Reference: Mori et al. Cancer Med. 2021;10:7988–95 [11]. Table 2The proportion of patients who died within 3 days based on the P3did-score (EASED study)

The P3did-score is the sum of 4 systems: nervous (decreased level of consciousness as indicated by RASS ≤ −2), cardiovascular (peripheral cyanosis, pulselessness of radial artery, and decreased u/o), respiratory (apnea, Cheyne-Stokes breathing, and respiration with mandibular movement), and musculoskeletal (inability to close eyelids, hyperextension of the neck, and drooping of nasolabial folds) systems. If any sign is present within each system, a score of 1 is given to the system, with the total score ranging from 0–4, and a higher score signifying a greater likelihood of death within 3 days. Reference: Mori M, et al. Cancer Med. 2021;10:7988–95 [11]. EASED, East-Asian cross-cultural collaborative Study to Elucidate the Dying process; P3did, prediction of 3-day impending death; RASS, Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale; u/o, urinary output. Table 3Recommended care strategies when communicating impending death Table 4Unanswered questions and future directions in prognostication of impending death References1. Ruegger J, Hodgkinson S, Field-Smith A, Ahmedzai SH. Guideline CommitteeCare of adults in the last days of life: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2015;351:h6631.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer NetworkPalliative care (version 2.2019 [Internet]. Plymouth Meeting, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2019. [cited 2019 Sep 2]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#supportive

3. Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Morita T, Hirai K, Uchitomi Y. Good death in cancer care: a nationwide quantitative study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1090–7.

4. Masterson MP, Slivjak E, Jankauskaite G, Breitbart W, Pessin H, Schofield E, et al. Beyond the bucket list: unfinished and business among advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27:2573–80.

5. Domeisen Benedetti F, Ostgathe C, Clark J, Costantini M, Daud ML, Grossenbacher-Gschwend B, et al. International palliative care experts’ view on phenomena indicating the last hours and days of life. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1509–17.

6. Hui D, dos Santos R, Chisholm G, Bansal S, Silva TB, Kilgore K, et al. Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients. Oncologist. 2014;19:681–7.

7. Hui D, Dos Santos R, Chisholm G, Bansal S, Souza Crovador C, Bruera E. Bedside clinical signs associated with impending death in patients with advanced cancer: preliminary findings of a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Cancer. 2015;121:960–7.

8. Hui D, dos Santos R, Chisholm GB, Bruera E. Symptom expression in the last seven days of life among cancer patients admitted to acute palliative care units. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:488–94.

9. Bruera S, Chisholm G, Dos Santos R, Bruera E, Hui D. Frequency and factors associated with unexpected death in an acute palliative care unit: expect the unexpected. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:822–7.

10. Bruera S, Chisholm G, Dos Santos R, Crovador C, Bruera E, Hui D. Variations in vital signs in the last days of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:510–7.

11. Mori M, Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Hatano Y, Yamaguchi T, Imai K, et al. Diagnostic models for impending death in terminally ill cancer patients: a multicenter cohort study. Cancer Med. 2021;10:7988–95.

12. Ikari T, Hiratsuka Y, Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Mori M, Uneno Y, et al. “3-Day Surprise Question” to predict prognosis of advanced cancer patients with impending death: multicenter prospective observational study. Cancer Med. 2021;10:1018–26.

13. Ito S, Morita T, Uneno Y, Taniyama T, Matsuda Y, Kohara H, et al. Incidence and associated factors of sudden unexpected death in advanced cancer patients: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Cancer Med. 2021;10:4939–47.

14. Yamaguchi T, Maeda I, Hatano Y, Suh SY, Cheng SY, Kim SH, et al. Communication and behavior of palliative care physicians of patients with cancer near end of life in three East Asian countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61:315–22.

15. Mori M, Morita T, Igarashi N, Shima Y, Miyashita M. Communication about the impending death of patients with cancer to the family: a nationwide survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8:221–8.

16. Morita T, Ichiki T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. A prospective study on the dying process in terminally ill cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1998;15:217–22.

17. Hui D. Prognostication of survival in patients with advanced cancer: predicting the unpredictable? Cancer Control. 2015;22:489–97.

18. Llobera J, Esteva M, Rifa J, Benito E, Terrasa J, Rojas C, et al. Terminal cancer. duration and prediction of survival time. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:2036–43.

19. Hui D, Kilgore K, Nguyen L, Hall S, Fajardo J, Cox-Miller TP, et al. The accuracy of probabilistic versus temporal clinician prediction of survival for patients with advanced cancer: a preliminary report. Oncologist. 2011;16:1642–8.

20. Amano K, Maeda I, Shimoyama S, Shinjo T, Shirayama H, Yamada T, et al. The accuracy of physicians’ clinical predictions of survival in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50:139–46.

21. Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:469–72.

22. Perez-Cruz PE, Dos Santos R, Silva TB, Crovador CS, Nascimento MS, Hall S, et al. Longitudinal temporal and probabilistic prediction of survival in a cohort of patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:875–82.

23. Selby D, Chakraborty A, Lilien T, Stacey E, Zhang L, Myers J. Clinician accuracy when estimating survival duration: the role of the patient’s performance status and time-based prognostic categories. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:578–88.

24. Hui D, Ross J, Park M, Dev R, Vidal M, Liu D, et al. Predicting survival in patients with advanced cancer in the last weeks of life: How accurate are prognostic models compared to clinicians’ estimates? Palliat Med. 2020;34:126–33.

25. Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, Englesakis M, Adhikari NK. The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2017;189:E484–93.

26. White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, Stone P. How accurate is the ‘Surprise Question’ at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15:139.

27. Hamano J, Morita T, Inoue S, Ikenaga M, Matsumoto Y, Sekine R, et al. Surprise questions for survival prediction in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Oncologist. 2015;20:839–44.

28. Ikari T, Hiratsuka Y, Yamaguchi T, Mori M, Uneno Y, Taniyama T, et al. Is the 1-day surprise question a useful screening tool for predicting prognosis in patients with advanced cancer?-a multicenter prospective observational study. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:11278–87.

29. Kim SH, Suh SY, Yoon SJ, Park J, Kim YJ, Kang B, et al. “The surprise questions” using variable time frames in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2022;20:221–5.

30. Chen YT, Ho CT, Hsu HS, Huang PT, Lin CY, Liu CS, et al. Objective palliative prognostic score among patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:690–6.

31. Gwilliam B, Keeley V, Todd C, Gittins M, Roberts C, Kelly L, et al. Development of prognosis in palliative care study (PiPS) predictor models to improve prognostication in advanced cancer: prospective cohort study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5:390–8.

32. Hamano J, Takeuchi A, Yamaguchi T, Baba M, Imai K, Ikenaga M, et al. A combination of routine laboratory findings and vital signs can predict survival of advanced cancer patients without physician evaluation: a fractional polynomial model. Eur J Cancer. 2018;105:50–60.

33. Maltoni M, Nanni O, Pirovano M, Scarpi E, Indelli M, Martini C, et al. Successful validation of the palliative prognostic score in terminally ill cancer patients. Italian Multicenter Study Group on Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:240–7.

34. Suh SY, Choi YS, Shim JY, Kim YS, Yeom CH, Kim D, et al. Construction of a new, objective prognostic score for terminally ill cancer patients: a multicenter study. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:151–7.

35. Nagasako Y, Suzuki M, Iriyama T, Nagasawa Y, Katayama Y, Masuda K. Acute palliative care unit-initiated interventions for advanced cancer patients at the end of life: prediction of impending death based on Glasgow Prognostic Score. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:1557–64.

36. Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Vashi PG, King J, Dahlk SL, Grutsch JF, et al. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle in clinical practice: implications for prognosis in stage IIIB and IV non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:37.

37. Norman K, Stobaus N, Zocher D, Bosy-Westphal A, Szramek A, Scheufele R, et al. Cutoff percentiles of bioelectrical phase angle predict functionality, quality of life, and mortality in patients with cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:612–9.

38. Barbosa-Silva MC, Barros AJ, Wang J, Heymsfield SB, Pierson RN Jr. Bioelectrical impedance analysis: population reference values for phase angle by age and sex. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:49–52.

39. Hui D, Moore J, Park M, Liu D, Bruera E. Phase angle and the diagnosis of impending death in patients with advanced cancer: preliminary findings. Oncologist. 2019;24:e365–73.

40. Hui D, dos Santos R, Reddy S, Nascimento MS, Zhukovsky DS, Paiva CE, et al. Acute symptomatic complications among patients with advanced cancer admitted to acute palliative care units: a prospective observational study. Palliat Med. 2015;29:826–33.

41. Seow H, Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Howell D, Dudgeon D, Atzema C, et al. Trajectory of performance status and symptom scores for patients with cancer during the last six months of life. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1151–8.

42. Suh SY, Won SH, Hiratsuka Y, Choi SE, Cheng SY, Mori M, et al. Assessment of changes in symptoms is feasible and prognostic in the last weeks of life: an international multicenter cohort study. J Palliat Med. 2022;25:388–95.

43. Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S. The Palliative Prognostic Index: a scoring system for survival prediction of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1999;7:128–33.

44. Hui D, Hess K, dos Santos R, Chisholm G, Bruera E. A diagnostic model for impending death in cancer patients: preliminary report. Cancer. 2015;121:3914–21.

45. Hui D. Unexpected death in palliative care: what to expect when you are not expecting. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:369–74.

46. Wilcock A, Crosby V. Hospices and CPR guidelines: sudden and unexpected death in a palliative care unit. BMJ. 2009;338:b2343.

47. Ekstrom M, Vergo MT, Ahmadi Z, Currow DC. Prevalence of sudden death in palliative care: data from the Australian palliative care outcomes collaboration. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52:221–7.

48. Scott K. Incidence of sudden, unexpected death in a specialist palliative care inpatient setting. Palliat Med. 2010;24:449–50.

49. Virdun C, Luckett T, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: a systematic review of quantitative studies identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families rank as being most important. Palliat Med. 2015;29:774–96.

50. Virdun C, Luckett T, Lorenz K, Davidson PM, Phillips J. Dying in the hospital setting: a meta-synthesis identifying the elements of end-of-life care that patients and their families describe as being important. Palliat Med. 2017;31:587–601.

51. Imai K, Morita T, Yokomichi N, Kawaguchi T, Kohara H, Yamaguchi T, et al. Efficacy of proportional sedation and deep sedation defined by sedation protocols: a multicenter, prospective, observational comparative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62:1165–74.

52. Mori M, Kawaguchi T, Imai K, Yokomichi N, Yamaguchi T, Suzuki K, et al. How successful is parenteral oxycodone for relieving terminal cancer dyspnea compared with morphine? A multicenter prospective observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62:336–45.

53. Mori M, Morita T, Matsuda Y, Yamada H, Kaneishi K, Matsumoto Y, et al. How successful are we in relieving terminal dyspnea in cancer patients? A real-world multicenter prospective observational study. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3051–60.

54. Hui D, De La Rosa A, Wilson A, Nguyen T, Wu J, Delgado-Guay M, et al. Neuroleptic strategies for terminal agitation in patients with cancer and delirium at an acute palliative care unit: a single-centre, double-blind, parallel-group, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:989–98.

55. Hui D, Frisbee-Hume S, Wilson A, Dibaj SS, Nguyen T, De La Cruz M, et al. Effect of lorazepam with haloperidol vs haloperidol alone on agitated delirium in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1047–56.

57. Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, Wal der S, Butow PN, Carrick S, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:507–17.

58. Jaturapatporn D, Kirshen AJ. Attitudes towards truth-telling about cancer: a survey from Thailand. Palliat Med. 2008;22:97–8.

59. Seo M, Tamura K, Shijo H, Morioka E, Ikegame C, Hirasako K. Telling the diagnosis to cancer patients in Japan: attitude and perception of patients, physicians and nurses. Palliat Med. 2000;14:105–10.

60. Syed AA, Almas A, Naeem Q, Malik UF, Muhammad T. Barriers and perceptions regarding code status discussion with families of critically ill patients in a tertiary care hospital of a developing country: a cross-sectional study. Palliat Med. 2017;31:147–57.

61. Martina D, Geerse OP, Lin CP, Kristanti MS, Bramer WM, Mori M, et al. Asian patients’ perspectives on advance care planning: a mixed-method systematic review and conceptual framework. Palliat Med. 2021;35:1776–92.

62. Mori M, Morita T. End-of-life decision-making in Asia: a need for in-depth cultural consideration. Palliat Med. 2020;269216319896932.

63. Haugen DF, Hufthammer KO, Gerlach C, Sigurdardottir K, Hansen MI, Ting G, et al. Good quality care for cancer patients dying in hospitals, but information needs unmet: bereaved relatives’ survey within seven countries. Oncologist. 2021;26:e1273–84.

64. Shimizu Y, Miyashita M, Morita T, Sato K, Tsuneto S, Shima Y. Care strategy for death rattle in terminally ill cancer patients and their family members: recommendations from a cross-sectional nationwide survey of bereaved family members’ perceptions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:2–12.

65. Mori M, Fujimori M, Hamano J, Naito AS, Morita T. Which physicians’ behaviors on death pronouncement affect family-perceived physician compassion? A randomized, scripted, video-vignette study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:189–97.

66. Yamashita R, Arao H, Takao A, Masutani E, Morita T, Shima Y, et al. Unfinished business in families of terminally ill with cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:861–9.

67. Mori M, Yoshida S, Shiozaki M, Morita T, Baba M, Aoyama M, et al. “What I did for my loved one is more important than whether we talked about death”: a nationwide survey of bereaved family members. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:335–41.

68. Shirado A, Morita T, Akazawa T, Miyashita M, Sato K, Tsuneto S, et al. Both maintaining hope and preparing for death: effects of physicians’ and nurses’ behaviors from bereaved family members’ perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:848–58.

69. Hui D, Mo L, Paiva CE. The importance of prognostication: impact of prognostic predictions, disclosures, awareness, and acceptance on patient outcomes. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2021;22:12.

70. Butow PN, Clayton JM, Epstein RM. Prognostic awareness in adult oncology and palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:877–84.

71. Mori M, Morita T, Imai K, Yokomichi N, Yamaguchi T, Masukawa K, et al. The bereaved families’ preferences for individualized goals of care for terminal dyspnea: what is an acceptable balance between dyspnea intensity and communication capacity? Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1:42–9.

72. Hui D, De La Rosa A, Urbauer DL, Nguyen T, Bruera E. Personalized sedation goal for agitated delirium in patients with cancer: balancing comfort and communication. Cancer. 2021;127:4694–701.

73. Mori M, Yamaguchi T, Matsuda Y, Suzuki K, Watanabe H, Matsunuma R, et al. Unanswered questions and future direction in the management of terminal breathlessness in patients with cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5(Suppl 1):e000603.

74. Uchida M, Morita T, Akechi T, Yokomichi N, Sakashita A, Hisanaga T, et al. Are common delirium assessment tools appropriate for evaluating delirium at the end of life in cancer patients? Psychooncology. 2020;29:1842–9.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||