INTRODUCTION

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) originating from primitive mesenchymal cells accounts for more than half of all soft tissue sarcomas in children. RMS can arise in any part of the body containing striated muscle, and its clinical manifestations depend on the primary site and tumor extent (1). Many studies show a slight male predominance, with two age peaks: 2~6 years and 15~19 years (1,2). Infants less than one year old and adolescents showed advanced tumor staging, unfavorable histopathology, and a poorer outcome than children aged 1~9 (3). In addition, the extent of disease at diagnosis, primary tumor location, histology, and treatment can influence prognosis, although few reports exist on specific outcomes in Korean patients. Here, we evaluated data on 77 children diagnosed with RMS in Korea over a 20-year period (from 1986 to 2005), including epidemiology, clinical and histopathologic features, treatment modalities, treatment results, and complications related to therapy. In addition, we identified prognostic factors that affect overall and event-free survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The medical records of 77 patients diagnosed with RMS between January 1986 and December 2005 at Seoul National University Children's Hospital, Seoul, Korea, were retrospectively reviewed. Specific diagnostic and therapeutic information, including primary tumor site, histological subtype, Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS) clinical group, treatment modality, extent of surgery, radiotherapy, and recent follow-up data were analyzed. Biopsies were performed in all patients before chemotherapy, and they were confirmed using immunohistochemistry (4). The age at diagnosis was assessed as a categorical variable at three levels, i.e., at <2, 2~9, or 10~19 years old.

1) Staging and pretreatment assessment of primary tumor

Pretreatment evaluation of disease extent was performed by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Metastatic spread was assessed by chest X-ray, chest CT, abdomen CT, bone scans, and bilateral bone marrow aspirates/biopsies. For tumor staging, the IRS clinical grouping classification was used (5).

2) Treatment

The treatment regimen changed from IRS-III to the Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) protocol in 1999. The IRS-III protocol consists of surgery and multiagent chemotherapy using vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and actinomycin D, with or without irradiation (6). Group III or IV RMS was treated with IRS-III regimen 35, group I with regimen 31, and group II with regimen 33. The framework of the POG-ICE protocol involves ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide (7). In cases of parameningeal (PM) RMS, radiotherapy and intrathecal chemotherapy (methotrexate, cytarabine, and hydrocortisone) were added. Radiation therapies for IRS Group III and IV were started at week 6 (except high-risk parameningeal primary tumors, which were treated from week 0) and treatment planning was based on age and tumor size at diagnosis. Radiotherapy was delivered according to the IRS-III recommendations (6). Informed consent was obtained from parents prior to therapy, which included consent for medical record review.

3) Tumor response evaluation

Tumor response was evaluated after 20 weeks of initial treatment (after 20 weeks of IRS-III induction chemotherapy or the 4th course of the POG-ICE regimen and radiotherapy) using imaging of the same fields as at diagnosis. Treatment response was defined as follows: complete response (CR) - no radiographic evidence of residual disease; partial response (PR) - more than 50% reduction in the sum of the products of maximum perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions; stable disease (SD) - less than a 50% reduction in tumor size or less than a 25% increase in any measurable tumor area. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as more than a 25% increase in measurable tumor size and/or the development of a new lesion or symptoms of osseous lesions.

4) Definition of end points

The results of this study are expressed in overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS). Overall survival time was defined as the interval between the date of diagnosis and the date of death (from any cause) or the date of last follow-up. EFS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis to one of the following: the date of starting alternative treatment because of disease progression, the date of relapse, the date of death, or the date of last follow-up, whichever occurred first. Relapse was identified by unequivocal imaging and/or biopsy confirmation. EFS and OS values for children who had not experienced an event of interest were censored at last contact dates.

5) Statistical methods and strategy

The most recent follow-up was March 2007, a minimum of 1 and maximum of 223 months from diagnosis. The relationship between each parameter (age, gender, IRS stage, primary tumor site, and pathological finding) and initial treatment response was examined by Pearson correlation analysis. EFS and OS curves were calculated using the Kaplan and Meier method (8). Differences between curves were analyzed using the log-rank test (9). The Cox proportional hazards model (10) was used to identify factors predictive of OS and EFS after adjusting for known prognostic factors. Statistical significance was accepted at the p<0.05 levels.

RESULTS

1) Patient and tumor characteristics

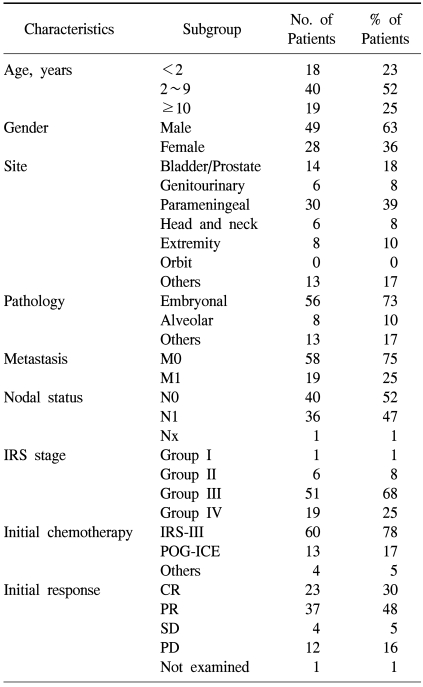

Patient clinical characteristics and IRS stage are shown in Table 1. The male-to-female ratio was 49:28, and the patient median age was 4.25 years (range, 4 months to 17.4 years). The most common primary tumor location was the PM site (30 patients; 39%), and embryonal histology the most common subtype (56 patients; 73%). One or more metastases at initial diagnosis were observed in 19 patients, and most commonly occurred in the lung (16 patients), bone (15 patients), bone marrow (5 patients), liver (2 patients), and other sites (7 patients). The proportion of IRS Group III (56 patients) and IV (19 patients) was 91%, indicating that the majority had advanced disease. An IRS-III protocol-based regimen was administered to 60 patients (78%) (41 patients corresponded to Group 3; 12 patients corresponded to Group 4; 6 patients were Group 2; 1 patient was Group 1). Thirteen patients (16.8%) were treated using a POG-ICE protocol (7 patients were group 3; 6 patients were group 4). The remaining 4 patients were initially diagnosed with other tumors (Ewing sarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, neuroblastoma), and were treated with other chemotherapeutic protocols. Radiotherapy was delivered at mean dose of 4,436 cGy in 79% (n=61) of patients.

2) Treatment outcomes

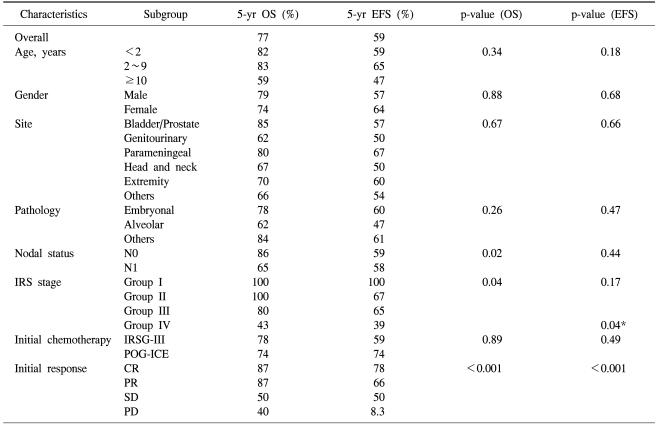

The median follow-up was 88 months after diagnosis. Twenty weeks after starting treatment, tumor response was evaluated. Complete response was observed in 23 patients (30%); partial response in 37 (48%); SD in 4 (5%); and PD in 12 (16%). IRS stage (p=0.030) was closely correlated with initial response to treatment. Table 2 displays Kaplan-Meier analysis results at 5 years after diagnosis. The 5-year OS for the 77 patients was 77% and the 5-year EFS was 59%. Although the 5-year survival for patients with localized or regional RMS was 88%, that of metastatic RMS was 43%. Thirty-five patients (45.5%) experienced at least one important event, i.e., disease recurrence in 21, death or hopeless discharge without remission in 13, and death from any cause in 3. Late adverse events (death, disease recurrence, and a second malignancy) occurred in 3 patients who had survived five years event-free. The last disease recurrence was observed at 87 months after RMS diagnosis. One patient died of cardiomyopathy at 164 months after RMS diagnosis; this male patient with metastatic RMS originating from the pelvis had been treated with anthracycline at a cumulative dose of 391 mg/m2 and 4,500 cGy of radiation to the chest and abdomen.

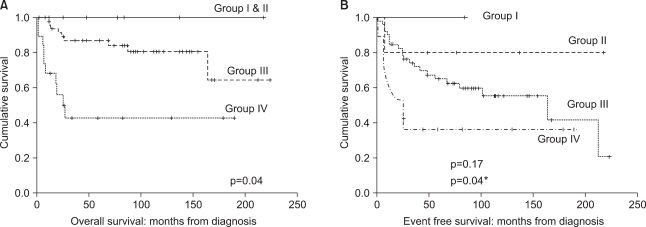

No significant differences were noted in OS and EFS according to age, gender, primary tumor site, or histopathology (Table 2), but the OS significantly changed with the IRS clinical group at diagnosis (p=0.04). Lymph node involvement at diagnosis also significantly affected survival (p=0.02). The chemotherapeutic modalities (IRS-III and POG-ICE) did not influence survival. The IRS clinical group at diagnosis significantly affected EFS (p=0.04, Fig. 1). In addition, OS and EFS rates closely related to initial treatment response (p<0.001, Fig. 2). Specifically, patients achieving CR or PR after initial therapy had higher OS and EFS than patients who did not, and that patient subset showed favorable OS (87%) and EFS (72%), as reported previously (11~13), while poor responders had a poor prognosis: 5-year OS and EFS were 38% and 17%, respectively. Treatment response (at 20 weeks) was an independent prognostic factor for survival according to Cox proportional hazard regression analysis (p<0.001) (Table 3). Treatment-related mortality occurred in 4 patients. One patient died from cardiomyopathy; two secondary to septicemia that developed during a period of neutropenia; and one developed a secondary malignancy (acute myeloid leukemia).

DISCUSSION

This study reviewed treatment outcomes of Korean RMS patients treated during the past 20 years in a single center. Patient age distribution, a slight male predominance, dominance of the embryonal subtype, and primary tumor locations were concordant with previous data (1,11,12). However, we observed a higher ratio (73%) of embryonal, tumors compared with 55% in other studies (5,6), but which was similar to other Korean data (72.4%) (14). In addition, there were higher proportions of group III and IV patients (66%, 26%) than IRS-III (48%, 16%) (6), perhaps due to delays in RMS diagnosis in Korean patients. Alternatively, this difference may reflect the fact that the patient sample originated at one of the largest cancer referral centers in Korea, which may have accumulated more advanced patients.

Age, histological tumor subtype, and primary tumor site can be important predictors of survival, but were not significantly related to survival here, perhaps due to small patient sample size. Further enrollment and more comprehensive analysis are needed.

Responses to induction chemotherapy did not influence failure-free survival in RMS when assessed at week 8, the initial response to induction chemotherapy (15). We assessed treatment response after induction and local control were complete at 20 weeks, and found a significant effect of response rate on OS and EFS. These results strengthen the argument to modulate therapies according to chemosensitivity and risk factors (16). For patients with favorable characteristics, risk-adapted treatment would reduce the intensity of chemotherapy or radiotherapy (6). Alternatively, poor responders with many risk factors would require further intensive or novel treatments, so as high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell rescue (16~18). However, retrospective analyses of patients with high-risk RMS failed to identify a clear survival advantage for intensive treatments (19,20). Thus, new treatment strategies are obviously needed, particularly for high-risk patients that respond poorly to treatment. Targeted therapies addressing chromosomal translocations or specific gene expression profiles may provide novel therapeutic opportunities for intervention in high-risk RMS (21,22).