AbstractPurposeThis is an ad hoc analysis of two phase II studies which compared the efficacy and safety of two taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel) combined with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and leucovorin (LV) in advanced gastric cancer.

Materials and MethodsPatients with advanced gastric adenocarcinoma who were untreated or had only received first-line chemotherapy, were treated with either paclitaxel (PFL; 175 mg/m2) or docetaxel (DFL; 75 mg/m2) on day 1, followed by a bolus of LV (20 mg/m2 days 1~3) and a 24-hour infusion of 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2 days 1~3) every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR) and the secondary endpoint included survival and toxicity.

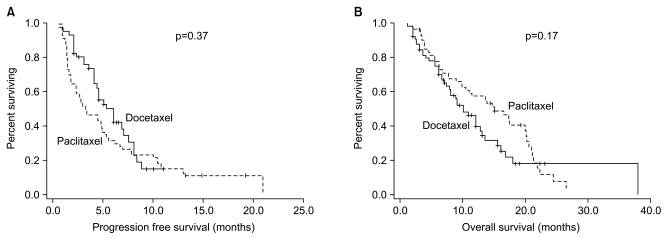

ResultsSixty-six patients received DFL (first-line [n=38]; and second-line [n=28]) and 60 patients received PFL (first-line [n=37]; and second-line [n=23]). The ORRs were not significantly different between the 2 groups (DFL, 26%; PFL, 38%). With a median follow-up of 9.5 months, the progression free survival was 5.2 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.2~6.5 months) for DFL and 3.3 months (95% CI, 1.3~5.5 months) for PFL (p=0.17). The overall survival was also comparable between the patients who received DFL and PFL (10.0 months [95% CI, 7.2~12.5 months] and 13.9 months [95% CI, 10.9~19.2 months], respectively; p=0.37). The most frequent grade 3~4 adverse event was neutropenia (DFL, 71%; PFL, 62%). DFL and PFL had different non-hematologic toxicities; specifically, grade ≥3 mucositis (5%) and diarrhea (3%) were common in DFL, while nausea/vomiting (15%) and peripheral neuropathy (5%) were common in PFL.

IntroductionStomach cancer shows a moderate degree of the sensitivity to anti-cancer drugs. According to randomized clinical trials which were conducted in patients with advanced stomach cancer, a combined anti-cancer treatment significantly had a prolonged survival period and an improvement of the quality of life as compared with the best supportive care group. To date, many treatment regimens have been developed to fulfill these objectives (1,2). Despite a great number of Phase III clinical trials, however, there are no established answers to the best combination of various anti-cancer drugs. To date, depending on the results of clinical trials and the preferences of researchers, the combination treatments based on 5-FU, anthracycline and cisplatin have been proposed as a standard treatment modality. But their effects and the degree of prolonging the survival period are not satisfactory yet. Considering the systemic status and a short survival period of patients with stomach cancer, the toxicity accompanied by the treatment occurs to a not negligible extent. This impedes the long-term treatment (3). Therefore, the development of anti-cancer treatments by which the toxicity can be lowered and the quality of life can be improved has been continually made (1). Such anti-cancer drugs that have recently been developed to improve the previous ones including oral 5-FU agents, oxaliplatin or irinotecan or to have new target have been reported to be efficacious and safe as compared with the previous ones. According to this, these drugs have been tested on clinical trials which are conducted in patients with stomach cancer.

Of these, taxane is a remarkable drug in the sense of new target in particular. Two representative taxane drugs include Docetaxel and paclitaxel, whose single use has been reported to commonly have a response rate of 17~25% in patients with progressive stomach cancer. Of these, the efficacy and safety of docetaxel have been demonstrated on randomized clinical trials about a combination therapy with anti-cancer drugs since the early stage. Through V325 study, a Phase III trial, a combination treatment of cisplatin +5-FU (CF) with docetaxel (DCF) showed that the survival period and quality of life were significantly improved. The occurrence of the toxicity of Grade 3~4 in severity proposed that the treatment dose and schedule should be re-considered to accept DCF as a standard treatment modality for cases of stomach cancer (5,6). For instance, Thus-Patience et al. proposed that a single use of DF except for cisplatin had an equivalent profile of the efficacy to epirubicin + cisplatin +5-FU (ECF) or DCF (2). According to various types of Phase II studies, a combination treatment with Paclitaxel produced a response rate of 32~66% and a survival period of 6~12 months (3-5). To date, however, almost no randomized clinical trials have been attempted to compare the efficacy of these regimen. These taxanes have a similar mode of action, and they also share the similar pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic characteristics. It has been proposed, however, that there are significant differences in the binding sites for tubulin, the degree of affinity, toxicity and the expression of cross-reactivity between the two drugs. In recent years, genomic studies have also shown that there is a difference between the two drugs based on the reports that the gene groups are different in association with the sensitivity of two drugs (6). However, clinical trials have been attempted to directly compare the efficacy and safety of twp drugs in a very limited scope. It is assumed that these studies can propose the baseline data for selecting the effective treatment drugs and exploring the prognostic indicators associated with the safety in patients. Given this background, the current paper reanalyzed the treatment outcomes of prospective anti-cancer therapy based on decetaxel or paclitaxel during the similar period in a similar group of patients in a single-institution setting (7,8).

Materials and Methods1 Patient eligibilityInclusion criteria for the current study are as follows: (1) A histologically/cytologically proven adenocarcinoma, (2) Metastatic or surgically-unresectable recurrent stomach cancer, (3) A lack of the previous history of palliative treatment (the adjuvant treatment following the radical surgery which was completed six months before is allowed) and patient who underwent the primary anti-cancer treatments for palliative purposes, (4) Age of 18 years or older, (5) Measurable or assessable lesions, (6) A performance of the maintenance of daily lives with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) of 0~2, (7) Patients whose hematologic, renal and hepatic profiles were sufficient (hemoglobin ≥9.0 g/dL, WBC ≥4,000/µL, neutrophils ≥2,000/µL, platelets≥100×103/µL, total bilirubin: ≤1.25×the upper limit of normal value (hepatic metastasis: ≤2.0×the upper limit of normal value), creatinine: ≤1.5×the upper limit of normal value, creatinine clearance ≥60 mL/min, AST/ALT: ≤3.0×the upper limit of normal value (hepatic metastasis: ≤5.0×the upper limit of normal value), alkaline phosphatase (ALP): ≤3.0×the upper limit of normal value (bone metastasis: ≤5.0×the upper limit of normal value).

In the current study, however, the following cases were all excluded: (1) Patients with duplicate cancer, (2) Patients with peripheral neuropathy of >Grade 2 based on National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria (NCI-CTC), (3) Patients with CNS metastasis, (4) Patients with uncontrolled chronic diseases.

Each treatment regimen was progressed following a receipt of written informed consent from patients prior to the study conduct.

2 Treatment planOn day 1, patients were intravenously given docetaxel 75 mg/m2 for an hour (DFL group) or paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 for three hours (PFL group). Following the completion of an intravenous infusion of Taxane, leucovorin 20 mg/m2 was intravenously administered within two hours. Then, 5-FU 1,000 mg/m2 was continually infused via an intravenous route (the overall dose of 5-FU: 3,000 mg/m2). Treatments were repeated every third week. In both groups, the pre-treatments for taxanes were performed with such traditional drugs as dexamethasone, H2 blocker and diphenhydramine.

In cases in which the hematologic or non-hematologic toxicity of >Grade 3 occurred, until a recovery was achieved to neutrophil counts ≥1,500/µL, platelet counts ≥100,000/µL or the severity of non-hematologic roxicity was lowered to Grade 1, an assessment was performed at a 1-week interval. Then, the anti-cancer treatment was delayed. For the next-cycle treatments, the dose of 5-FU and taxane was decreased by 20% each. In the Docetaxel treatment group, considering a higher incidence of the hematologic toxicity which has already been known, the preventive use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was performed for five days after four days following the initiation of anti-cancer treatments. In the paclitaxel group, the preventive use of G-CSF was not considered. Only in cases in which the neutropenia of >Grade 4 occurred, based on the judgement of physicians, it was administered for the therapeutic purposes. In cases in which the administration of drugs was delayed during a more than 4-week period due to the drug-related toxicities or those in which the dose reduction by more than 40% was necessary because of the plan of dose lowering, the corresponding patients were dropped out of the current trial. The anti-cancer treatment was persisted up to 12 cycles unless there were disease progression, uncontrolled toxicity and a withdraw of written informed consent. Thereafter, at a 3-month interval, the disease progression and patient survival were followed up.

3 Patient evaluationIn all the patients, as the baseline assessment prior to the treatment, physical examination, complete blood count (CBC), serum chemistries, urine analysis and EKG were performed. A radiographic assessment of the tumor was also performed within four weeks prior to the treatment. During the treatment period, patients underwent CBC on a weekly basis. Physical examination, the status of the performance of daily lives and serum chemistries were performed every cycle. An imaging study was performed every second cycle (six weeks). An endoscopy was performed to confirm a complete remission.

In our patients, the treatment response was assessed according to guidelines specified on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) Committee. Measurable lesions were defined as those whose longest diameter exceeded 10 mm on spiral CT scans. In cases in which the findings of over partial response were observed on an assessment of the treatment response during the treatment, lesions were re-confirmed following two cycles. Cases in which the clinical deterioration was observed both clinically and radiologically even prior to the completion of the first 2-cycle treatment or those in which the radiologic tumor evaluation was performed more than once following the completion of 2-cycle treatment were all considered to have a possibility of performing an assessment of the tumor response. A progression Free Survival (PFS) was defined as disease progression since the date of treatment initiation, death occurrence with no respect to the cause or the development of secondary cancer. The overall survival (OS) was defined as the period ranging from the date of treatment initiation to that of patients' death. The time to response was defined as the period ranging from the date of treatment initiation to that when a remission (partial or complete) was first achieved. A response duration was defined as the period ranging from the date when a remission was first noted on an assessment of the treatment response to that when the recurrence or disease progression were confirmed. Drug toxicity was evaluated based on the NCI-CTC (version 3.0), for which the date of toxicity onset, that of completion and a causal relationship with the drugs were specified.

4 Statistical considerationThe response rate was analyzed based on intent-to-treat analysis which was performed in all the patients who underwent treatment following the registration with the clinical trial and per protocol analysis in those who underwent tumor evaluation at least once. The survival period and toxicity were analyzed in all the patients who received the anti-cancer treatment at least once. The current study was ad hoc retrospective analysis following the prospective one. A comparison of the clinical characteristics between the two groups was made using chi-square test. A comparison of the overall response rate was made using t-test. Besides, a comparison of the variables associated with time was made using Log-rank test based on Kaplan-Meier method.

Results1 Patient characteristicsDuring a period ranging from October of 2001 to April of 2005, a total of 126 patients (DFL=66, PFL=60) were enrolled in the current study. In the DFL group, seven patients withdrew a written informed consent before completing two cycles. These patients were excluded from an assessment of the tumor response. In the PFL group, four patients were ruled out for same reasons. Beside, all the patients in the DFL group had measurable lesions in 59 patients excluding seven mentioned above, an analysis of the response rate and survival could be performed. In the PFL group, ten patients had measurablbe, non-lesional, assessable areas. These patients were excluded from an analysis of the response rate, but were included in an analysis of the survival. A comparison of the baseline clinical characteristics was made between the treatment groups, whose results were represented in Table 1. For the primary treatment, the current drugs were administered to 38 patients (58%) of the DFL group and 37 patients (62%) of the PFL group (p=0.640). Besides, there were also no significant differences in other clinical characteristics between the two groups (Table 1). Major organs of metastasis include intrabdominal lymph node, liver and ovary. The proportion of patients who were suspected to have peritoneal dissemination on CT scans was 27% in the DFL group and 28% in the PFL group.

2 Treatment and dose intensityThe administration was done at a total of 260 cycles (median 4: range 1~10) in the DFL group and 280 cycles (median 4: range 1~12) in the PFL group. These results showed that there was no significant difference in the cycle of anti-cancer treatment between the two groups (Table 2). In the DFL group, however, the cycles at which the treatment was delayed were 90 (35%) and this was significantly higher than 50 (18%) seen in the PFL group (p=0.02). Causes of the delayed treatment include the hematologic toxicity (79%), which was the most prevalent one, non-hematologic toxicity (13%) and patients' own will (7%). The median value of the dose intensity of Docetaxel was 21 mg/m2/week (range 13~25 mg/m2/week). The dose intensity of paclitaxel was 53 mg/m2/week (range 37~58 mg/m2/week). The relative dose intensity was 0.86 and 0.91 in the corresponding order, which was significantly lower in the DFL group (p=0.02). The dose intensity of 5-FU was 857 mg/m2/week (range 545~1,000 mg/m2/week) and 913 mg/m2/week (range 640~1,000 mg/m2/week) in the corresponding order, which was significantly lower in the DFL group (p=0.03).

3 Objective responseThe overall response rate which was measured only in patients who had measurable lesios, of total patients, was 31%. Following an analysis which was performed based on an intent-to-treat principle, the proportion of patients who showed more than a partial remission was 26% (95% CI, 15~37%) in the DFL group and 38% (95% CI, 20~44%) in the PFL group (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the response rate between the two groups (p=0.32). These two groups were subdivided into two subgroups: the primary treatment group and the secondary treatment group. According to this, the response rate of the primary treatment group in both groups was 34% and 41% (p=0.57) and that of the secondary treatment group was 14% and 32% (p=0.06) in the corresponding order. These results indicate that the response rate was significantly higher in the PFL group, but this did not reach a statistical significance. The median time to response was 2.0 months (range 1.5~6.0 months) in the DFL group and 2.5 months (range 1.5~5.0 months) in the PFL group, which showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups. The period during which the response was persisted was 3 months (range 0.8~10.8 months) in the DFL group and 5.4 months (range 2.6~8.2 months) in the PFL group. But this difference did not reach a statistical significance (p=0.25) (Table 4).

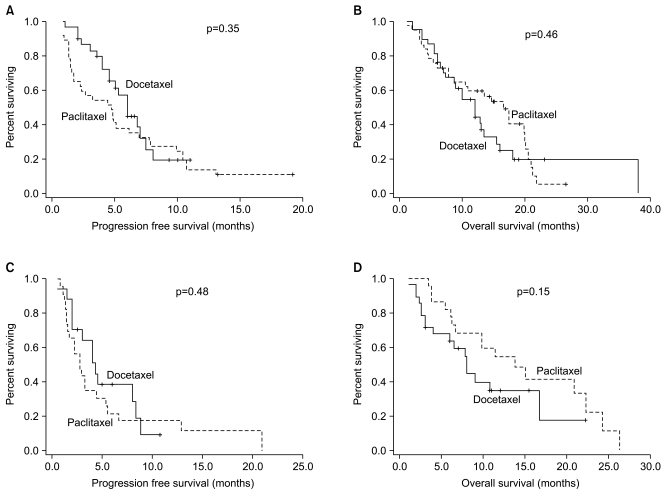

4 Survival analysisMedian follow-up period was 9.5 months at the time of survival analysis. A comparison of the progression-free survival and the overall survival period was made between the two groups, whose results were represented in Table 4. A disease progression was seen in 54 patients of the DFL group and 53 patients of the PFL group. In each group, 44 patients died. In total patients who were treated with taxane, median period of progression-free survival was 4.5 months (95% CI, 3.5~5.5 months). It was also evaluated in each treatment group, which was 5.2 months (95% CI, 4.2~6.5 months) in the DFL group and 3.3 months (95% CI, 1.3~5.5 months) in the PFL group (Fig. 1A). A median period of progression-free survival was examined in 50 patients of the PFL group, who had measurable lesions, and it was 2.9 months (95% CI, 1.4~4.0 months). This was not significantly different from a median period of progression-free survival which was examined in total patients of the PFL group (p=0.75) (Table 4). Besides, a median period of progression-free survival was also examined only in patients who received the primary treatment, which was 6.0 months (95% CI, 4.6~7.3 months) in the DFL group and 4.8 months (95% CI, 2.8~6.8 months) in the PFL group (p=0.35) (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, a median period of progression-free survival was also examined only in patients who received the secondary treatment, which was 4.0 months (95% CI, 2.7~5.3 months) in the DFL group and 3.0 months (95% CI, 2.0~4.0 months) in the PFL group. These differences did not also reach a statistical significance (p=0.48) (Fig. 2C).

In total patients, the median value of overall survival was 12.0 months (95% CI, 9.1~14.9 months). In each treatment group, the median survival period was 10.0 months (95% CI, 7.2~12.5 months) in the DFL group and 13.9 months (95% 10.9~19.2 months) in the PFL group (Fig. 1B). The median survival period was also evaluated only in patients of the PFL group, who had measurable lesions, and it was 13.8 months (95% CI, 8.0~19.6 months). This was not significantly different from the median survival period which was evaluated in total patients of the PFL group (p=0.99) (Table 4). Besides, the overall survival was also evaluated only in patients who received the primary treatment, which was 11.7 months (95% CI, 8.7~14.2) in the DFL group and 16.5 months (95% CI, 11.3~21.8) in the PFL group (p=0.46) (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the overall survival was also evaluated only in patients who received the secondary treatment, which was 8.0 months (95% CI, 3.5~12.4) and 13.8 months (95% CI, 7.3~20.3) in the corresponding order (p=0.15) (Fig. 2D).

5 ToxicityOf patients of the DFL group, one died of febrile neutropenia and septic shock following the first cycle of treatment. In the PFL group, however, there were no drug-related deaths. In both groups, the most common toxicities of Grade 3~4 in severity include neutropenia. A Grade 4 neutropenia occurred at an incidence of 56% in the DFL group, which was significantly higher than 37% seen in the PFL group (p=0.03) (Table 5). Febrile neutropenia occurred at an incidence of 12% in the DFL group, which was higher than 3% seen in thePFL group. But this difference did not reach a statistical significance (p=0.07). All of these cases were recovered to a level of >Grade 1 using the conservative treatment. There was no significant difference in the incidence of Grade 3~4 neutropenia between the primary and secondary treatment groups (p=0.59).

Grade 3~4 non-hematologic toxicities occurred in a total of ten patients, and this incidence was relatively lower than the hematologic toxicities. Non-hematologic toxicities showed a variability depending on the type of taxanes which were administered. In the DFL group, the major drug-related toxicities include mucositis (5%) and diarrhea (3%). In the PFL group, however, they include nausea/vomiting (8%) and neurotoxicity (5%).

DiscussionThe current study is an ad hoc analysis of two independent studies which were conducted in a single-institution setting in patients with progressive stomach cancer. It was conducted in patients who had similar inclusion criteria during the similar period. DFL treatment included only patients who had measurable lesions, whose primary endpoint was the response rate. The preventive use of G-CSF was allowed. But PFL treatment had the primary endpoint of progression-free survival. Based on this, the number of patients who would be recruited was determined. Accordingly, ten patients with assessable lesions were also included. The therapeutic use of G-CSF was solely allowed. As mentioned herein, two Phase II studies had no identical study design in a detailed matter. But there were no significant differences in the clinical characteristics between the two groups. The treatment dose and interval were completely identical in drugs other than taxanes. The pharmacodynamic titer of two types of taxanes was similar. Based on these findings, a retrospective comparison of two treatment regimens would not be problematic. It is therefore assumed that the current data should be understood based on the extended limitations of retrospective studies.

To date, only a limited number of studies have compared the efficacy of paclitaxel and docetaxel. The results were that the efficacy of these drugs varied depending on inclusion criteria, the establishment of attempted endpoints and the viewpoint of interpretation. According to ECOG 1594 study which was conducted in patients with lung cancer, following a combination therapy using cisplatin and taxane, there were no significant differences in the response rate and survival period between the two drugs. Neutropenia of Grade 3~4 in severity and neurotoxicity occurred at a similar incidence (9,10). By contrast, according to Phase III studies which have been conducted in patients with breast cancer, as compared with paclitaxel, docetaxel had an excellent profile of the response rate and the progression-free survival. It has also been reported, however, that the incidence of side effects was relatively higher following the administration of docetaxel. Following a concomitant use with carboplatin in patients with ovarian cancer, both drugs had a similar profile of the efficacy and survival. The severity of docetaxel treatment has been reported to be significantly higher (11,12). But the greatest limitation of randomized trials that are conducted as the primary treatment in patients with stomach cancer is that the role of taxane has not been established as a standard anti-cancer treatment as compared with the above-mentioned cancers stomach cancer. Up to present, regarding the anti-cancer treatments for stomach cancer, as compared with 5-FU monotherapy, the excellent treatment outcomes have not been reported following the use of ECF in Europe including the UK, following the use of CF in Asia and following the use of CF according to JCOG9205 in Japan. According to this, according to 5-FU monotherapy or the results of recent trials such as JCOG9912 and SPIRITS, the anti-cancer treatments based on S-1 have been considered as a standard modality with the validity (13,14). In recent years, DCF therapy has been indicated as a possible new standard treatment modality. Due to a higher incidence (69%) of side effects of Grade 3~4 in severity and that (82%) of neutropenia, there are many obstacles that such drugs can be used as such in a clinical setting (15). Besides, many debates have been made regarding whether concomitant treatment regimens including capecitabin, proposed on Phase III studies in Korea, could be established as a standard modality. Accordingly in the current study, it was difficult to recruit patients who had no past history of anti-cancer treatment and to interpret the results. Accordingly, the interpretation of study results does not mean that either docetaxel or paclitaxel is excellent for the treatment of stomach cancer. Besides, it also pose a question whether a concomitant medication with 5-FU excluding cisplatin would produce an equivalent profile of the efficacy to DCF. There are almost no studies that have compared the efficacy of taxane in patients with stomach cancer. In a situation where there are a series of the pre-clinical evidences that there is a discrepancy in the pharmacodynamic characteristics between the two drugs contradictory to what has been predicted, the current study might be of significance in that it would provide the baseline data for the conduct of interventional studies and clinical ones that predict the efficacy/safety of drugs in patients with progressive stomach cancer (6). Actually, we're currently conducting the clinical trials to confirm the cross-reactivity of taxanes in patients with stomach cancer and a series of interventional studies to examine single nucleotide polymporphism (SNP) of binding sites for β-tubulin or the difference in the sensitivity of inactivation enzymes.

In the current study, despite the limitations mentioned above, DFL and PFL have been demonstrated to have the efficacy and safety for their primary and secondary treatments. The response rate and survival period that were seen in both groups are similar to those seen in a previous single study and a phase II study which was conducted by Park et al. (16). Because a statistical titer was lowered due to a limited number of enrolled patients, a meticulous analysis of the difference in the treatment outcomes between the two groups could not propose the results. In the DFL group, however, the response rate, the side effects and the overall survival rate were unfavorable as compared with the PFL group. It was also shown, however, that a progression-free survival was prolonged. By contrast, despite a shorter progression-free survival, the overall survival was favorable in the PFL group. The former indicates that the tumor evaluation was delayed every second cycle due to the prevalence of dose lowering or delayed treatment. Besides, the latter indicates that the PFL treatment is more advantageous for the compliance or the maintenance of systemic status and thereby provides more opportunities for salvage anti-cancer therapy. Although not conducted in the current study, an assessment of the quality of life or an analysis of the time point of the onset of side effects would further reflect these characteristics. Furthermore, a 3-day consecutive intravenous infusion of 5-FU, its resulting prolongation of length of hospital stay and the role of a low-dose leucovorin could also be questionable. In recent years, a biweekly or weekly schedule of 5-FU treatment where a prompt infusion is coupled with a sequential one have frequently been used to treat patients with colorectal cancer or stomach cancer. Based on the recent reports that a weekly administration of taxanes secured the dose intensity and its efficacy was not inferior to that of previous treatment regimens, it can therefore be inferred that the dose and schedule of the current treatment regimen should be further discussed considering the side effects and compliance (17).

In the current study, there were clear differences in the frequency and degree of toxicity between docetaxel and paclitaxel. In the DFL group, although the preventive use of G-CSF was allowed according to the results of previous clinical studies, 71% of patients complained of Grade 3~4 neutropenia and febrile neutropenia. This might lead to the delayed treatment and the decreased dose intensity. Of note, 60% of patients of the PFL group also complained of Grade 3~4 neutropenia. This Fig was significantly greater than approximately 10~30% which has been reported on other studies (4,18). This might be partially explained by the following reasons: (1) A hematologic examination was meticulously performed on a weekly basis. (2) The age of patients who were enrolled in the PFL group was relatively higher (>65 years of age, 20%). (3) Patients had a poor performance of the daily lives (ECOG 2, ≥50%).

However, most of the neutropenia occurring in the PFL group were easily resolved by the administration of G-CSF. The proportion of cases in which neutropenia led to the occurrence of febrile neutropenia was 3%, which was relatively good as compared with 12% seen in the docetaxel group.

ConclusionThis study suggests a concomitant treatment regimens such as DFL or PFL which were performed in patients with progressive stomach cancer showed no significant differences in the treatment effect and safety. Both treatment regimens showed the effectiveness which was equivalent to the previous ones.

In the DFL group, neutropenia and its resulting delayed anti-cancer treatment, decreased dose and the difference in non-hematologic toxicity could also be mentioned as the major difference between the two treatment regimens. In the current study, however, it could not be determined whether there is a significant superiority between docetaxel and paclitaxel in patients with progressive stomach cancer. To do this, the standard treatment regimens should be established in patients with progressive stomach cancer. Moreover, conclusions should be drawn through a comparison based on randomized trials. Before then, further studies should continually be conducted to examine the detailed pharmacodynamic profile and resistance mechanisms of docetaxel and paclitaxel. Besides, further pharmacogenmic studies are also warranted to provide a detailed explaination about the effectiveness and toxicity of each drug.

References1. Lee JA, Yoon SS, Yang SH, Kim S, Heo DS, Bang YG, et al. FAM versus etoposide, adriamycin, and cisplatin: a random assignment trial in advanced gastric cancer. J Korean Cancer Assoc. 1993;25:461–467.

2. Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Repp M, Kingreen D, Hennesser D, Micheel S, et al. Docetaxel and continuous-infusion fluorouracil versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil for advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:494–501. PMID: 15659494

3. Kim YH, Shin SW, Kim BS, Kim JH, Kim JG, Mok YJ, et al. Paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil, and cisplatin combination chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;85:295–301. PMID: 10023695

4. Murad AM, Petroianu A, Guimaraes RC, Aragao BC, Cabral LO, Scalabrini-Neto AO. Phase II trial of the combination of paclitaxel and 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer: a novel, safe, and effective regimen. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:580–586. PMID: 10597742

5. Bokemeyer C, Lampe CS, Clemens MR, Hartmann JT, Quietzsch D, Forkmann L, et al. A phase II trial of paclitaxel and weekly 24 h infusion of 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8:396–399. PMID: 9180395

6. Jung JJ, Jeung HC, Chung HC, Lee JO, Kim TS, Kim YT, et al. In vitro pharmacogenomic database and chemosensitivity predictive genes in gastric cancer. Genomics. 2009;93:52–61. PMID: 18804159

7. Jeung HC, Rha SY, Kim YT, Noh SH, Roh JK, Chung HC. A phase II study of infusional 5-fluorouracil and low-dose leucovorin with docetaxel for advanced gastric cancer. Oncology. 2006;70:63–70. PMID: 16446551

8. Im CK, Jeung HC, Rha SY, Yoo NC, Noh SH, Roh JK, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel combined with infusional 5-fluorouracil and low-dose leucovorin for advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:315–321. PMID: 18026677

9. Rigas JR. Taxane-platinum combinations in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a review. Oncologist. 2004;9:16–23. PMID: 15161987

10. Esteban E, Gonzalez de, Fernandez Y, Corral N, Fra J, Muniz I, et al. Prospective randomised phase II study of docetaxel versus paclitaxel administered weekly in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1640–1647. PMID: 14581272

11. Jones SE, Erban J, Overmoyer B, Budd GT, Hutchins L, Lower E, et al. Randomized phase III study of docetaxel compared with paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5542–5551. PMID: 16110015

12. Vasey PA, Jayson GC, Gordon A, Gabra H, Coleman R, Atkinson R, et al. Phase III randomized trial of docetaxel-carboplatin versus paclitaxel-carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy for ovarian carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1682–1691. PMID: 15547181

13. Imamura H, IIishi H, Tsuburaya A, Hatake K, Imamoto H, Esaki T, et al. Randomized phase III study of irinotecan plus S-1 (IRIS) versus S-1 alone as first-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer. ASCO Meeting Proc. 2007;25:S18.

14. Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215–221. PMID: 18282805

15. Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko V, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–4997. PMID: 17075117

16. Park SH, Lee WK, Chung M, Lee Y, Han SH, Bang SM, et al. Paclitaxel versus docetaxel for advanced gastric cancer: a randomized phase II trial in combination with infusional 5-fluorouracil. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:225–229. PMID: 16428942

17. Park SR, Kim HK, Kim CG, Choi IJ, Lee JS, Lee JH, et al. Phase I/II study of S-1 combined with weekly docetaxel in patients with metastatic gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1305–1311. PMID: 18362939

18. Yeh KH, Lu YS, Hsu CH, Lin JF, Hsu C, Kuo SH, et al. Phase II study of weekly paclitaxel and 24-hour infusion of high-dose 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of recurrent or metastatic gastric cancer. Oncology. 2005;69:88–95. PMID: 16088236

Fig. 1Survival curves of all patients. (A) Progression free survival (PFS), (B) overall survival (OS).

Fig. 2Survival curves according to previous treatment. (A) Progression free survival of first-line treatment, (B) overall survival of first-line treatment, (C) progression free survival of second-line treatment, (D) overall survival of second-line treatment.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||